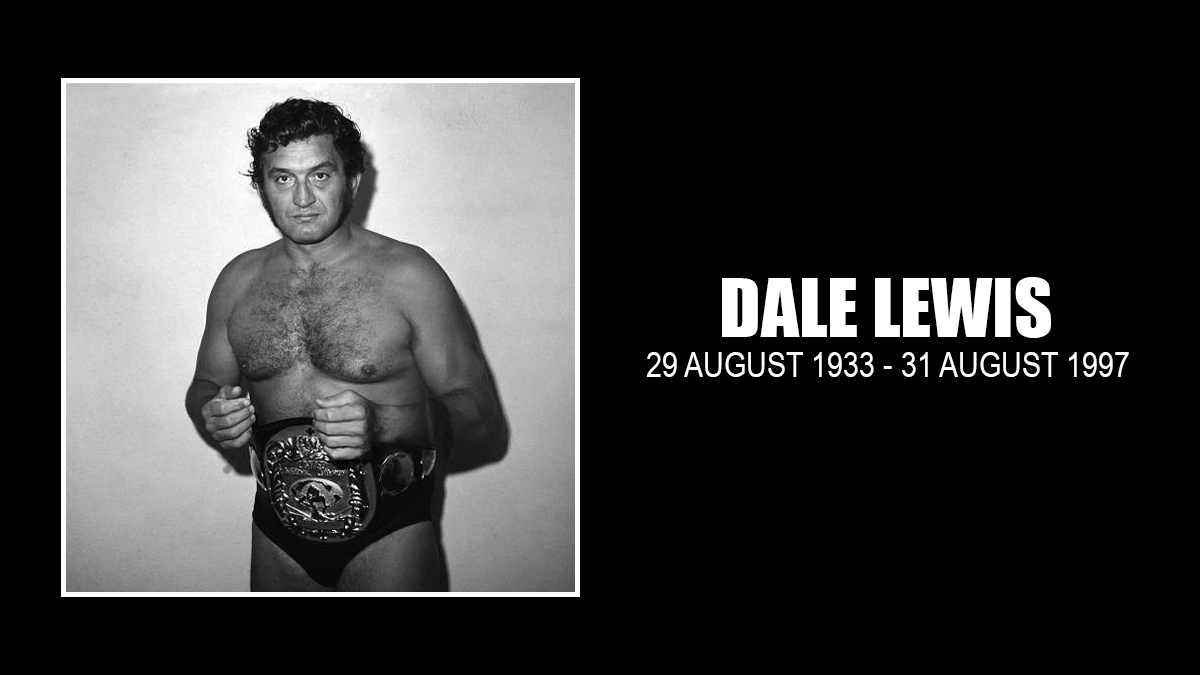

To make an Olympic team in any sport is a great accomplishment; to make an Olympic team within six months of taking up a sport is incredible. Yet Dale Lewis did just that in 1956 in Greco-Roman wrestling.

Pro wrestling fans will remember Lewis as ‘The Professor’ Dale Lewis, or in tag teams with his ‘brother’ Gene Lewis (aka Cousin Luke). But he accomplished far more in his stint as an amateur than he ever did as a pro.

Lewis was born in Rib Lake, Wisconsin, and grew up in Milwaukee. Always an athlete, he went to Marquette University on two athletic scholarships, one for basketball and one for football. But he dropped out after just a year to enter the Marine Corps.

It was in the Marines that Lewis learned amateur wrestling.

“Within six months, he qualified as an alternate to the ’56 Olympics. Isn’t that amazing? I mean, you just don’t pick up any sport in a year,” said Gene Petit, aka Gene Lewis, in Whatever Happened to … #44.

Dale travelled with the U.S. Olympic team to the Games in Melbourne, Australia and, under coach Joe Scalzo, did not place as a heavyweight.

Upon his return to the United States, and his discharge from the Marines, Lewis enrolled at the University of Oklahoma. Having come back to school, he was senior to his teammates, one of which was future pro wrestler and promoter Bill Watts.

“Dale is a really a neat guy if you get to know him. It was hard to get to know Dale. He was older than we were,” Watts said.

Watts had come onto the wrestling team from the football squad, and fought to establish a place on the heralded team. He credits Lewis with doing just enough to win when necessary; as he was as a pro wrestler, Lewis wasn’t an aggressive showman. He did what he had to in order to come out on top.

“Dale understood his bit, and his bit was to be real defensive and to make people shoot in on him. He would capitalize on that, and he won two national championships that way, so it worked,” Watts said. “I came out from football to wrestling, so I had to beat him off the team. So the deck was a wee bit stacked because he didn’t have to beat me. That really played into his hands, where he could stand on the edge of the mat, and if I shot and got something, he could step off the mat. And if I didn’t, he’d have a chance of countering me.

“Often times in tryouts-back when we were in college, matches were nine minutes, three three-minute periods-and ours sometimes went 25 minutes extensions before he’d finally catch me and beat me. He kept beating me off the team. This is before I lifted weights, before I was in the car-train wreck, before I had the tremendous change in me. Dale and I competed every day. I could pretty well beat him every day. But when it got down to tryouts, he knew what to do and had the maturity to do it. He didn’t get flustered no matter how people were trying to pressure him.”

Jack Brisco, the 1965 NCAA heavyweight wrestling champion, explained Lewis’ style in his book Brisco (Culture House Books, 2003):

“Although he was a two-time national champion, Lewis did not have much of a reputation as an amateur. His style on the mat was totally defensive, much like that of Larry Lane, who just closed up and wouldn’t wrestle me in the semi-finals of the 1965 NCAA Championships. He was big and slow and would confine his actions to the edge of the mat and just wait until his opponent would tire, get frustrated, or become desperate and make a mistake. Inevitably, that is exactly what would happen and one mistake is all Dale would need to nail his foe.

“Dale was at his best in the bottom position. He could escape from anyone and he could ride fairly well. In most of his matches he would take the bottom position, escape for one point and try to take the guy down; if not he would take the top position in the next period and ride his opponent and gain a point that way, so most of his matches would end 2-1. The rest of the time he would just try to keep from getting taken down or stepping off the mat.”

The 1960 NCAA Collegiate Championships were held at the University of Maryland, and Lewis won the heavyweight division over Sherwyn Thorson of Iowa (second), John Oberly of Pennsylvania State (third), and Rory Weber of Northwestern University (fourth).

In 1961, the finals were at Oregon State University. Lewis topped Ted Ellis of Oklahoma State (second), Rory Weber of Northwestern University (third) and John Oberly Pennsylvania State (fourth).

Watts recalled Lewis’ poise in one of the finals. “In one of the national championship matches, he was behind in the match. All the guys on the team are screaming to him, ‘Shoot, shoot, shoot.’ He never did shoot. The guy lost track of the fact that he was ahead, that he was wrestling. He shot on Dale and Dale countered him and won the title. So a lot of that was strategic.”

Lewis made the American Olympic squad in Greco-Roman Wrestling in 1960 as well. He travelled with the team to Rome, Italy, but again, did not place in the heavyweight division under coach Briggs Hunt. (To put Lewis’ accomplishments in Greco-Roman in perspective, no American placed in the Top 8 in Olympic competition from Greco-Roman’s debut in 1924 in Paris until the boycotted Games of 1984 in Los Angeles. The first U.S. medalist was Dennis Hall in 1996, with a silver.)

His Olympic experiences were unique among his teammates at Oklahoma, but it wasn’t as big a deal as it might be today. “You’ve got to realize that back then, the Olympics were like something in Never-Neverland, because Olympic style wrestling was so totally different than collegiate style. We were all under collegiate wrestling. You only switched over to what they called Olympic style for a short time. It was so totally different,” said Watts, adding that the coaches didn’t push Olympic style either.

Even years later, after the rigors of the pro circuit, Lewis didn’t bring up his Olympic or NCAA accomplishments much.

“Dale, he followed the Bible’s tutelage: Let someone else brag about you. … Dale never bragged about his tutelage, his medals and the rest of the stuff he won. You’d have to pump him,” said Dutch Savage.

Fellow Olympian Bob Roop (Mexico, 1968, Greco-Roman) concurred. “We never talked about it. I don’t know why. Jack Brisco was a pal of mine when I first started. He had been an NCAA champion, but we didn’t talk about that either. Maybe once in a while maybe for a few minutes, talking about some guy we knew in common or about a coach or a meet or team we’d both wrestled against.”

After finishing up at Oklahoma University, Dale Lewis debuted as a pro–billed from the University of Oklahoma–and was quickly pushed in the AWA, promoted by another former Olympian Verne Gagne (U.S. Greco-Roman team, 1948 London). Lewis would team with Pat Kennedy (Bobby Graham) to claim the AWA tag titles from Hard Boiled Haggerty & Bob Geigel on November 16, 1961 in Rochester, MN, but the team would lose them a week later to Bob Geigel & Otto Von Krupp (Boris Malenko).

As a pro, Lewis was best known in Florida and the Pacific Northwest, but had stints in the Bahamas, Puerto Rico, and Calgary.

“As slow as he was on the mat, he was just as slow in the ring,” recalled Jack Brisco in his autobiography. “He came to Florida as a professional, as well. Remember, Eddie liked the boys with an amateur background so two national titles made Dale all the more appealing to him. And appealing he was. He made the perfect heel as he became ‘The Professor’ Dale Lewis.”

Dutch Savage worked with ‘The Professor,’ and chuckled at some of the memories. “Dale was a sweetheart, Dale was a big pussycat. Tear your head off and put it on your foot if he didn’t like it, but he was just a big pussycat. When we brought him in here as Professor Dale Lewis, I worked for about a year with him. He put a lot of hickeys on me. He used to potato me for not working very hard. I’d say, ‘Why get up? We’ve got a top wristlock, we’ve got people in the ring.’ ‘Shut-up and lay down!’ And he’d start pounding on me. ‘C’mon, get up and go to work!’ He was a character.”

Bob Roop recognized the difficulties of turning pro after a successful amateur career, and battled Lewis after his stint in the 1968 Mexico City Olympics. “One of the things that was common for the boys, the pro wrestlers, to say — and it was true in many cases — was that an amateur will never make it as a top pro. He might make a living, but he’ll never be a top pro. In most cases, that’s true. Guys already have a persona that’s grounded in a lot of sweat and toil to get to the Olympic level. It’s hard to shove that aside and really pretend well to be someone else.”

“Dale didn’t ever make it to what I call the big-time elite, where he was a big star in the big box office areas,” said Watts.

Roop saw it the same way. “Dale had to be a pro that was just so-so. I’m not knocking him, but when I first began, I was having matches with him and here I was green as grass, I didn’t have a clue what I was doing out there, but I would have matches with other guys who were much less athletic, older, not in as good of shape, that would be great matches. I would have these matches with Dale, and people would tell me ‘You ought to be ashamed of yourself,’ even though I beat him. … He didn’t know how to make me look good, and I didn’t know to do that myself.”

To Dutch Savage, the difficulty lay in knowing what to do with him. “You let him do his intellectual interviews-he hardly ever raised his voice. It was excruciatingly good. What you had to do, you had to bring in a Beat The Champ thing. That’s what we did. Beat The Champ is when you get the strap, anybody from the audience can challenge the Pacific Northwest champion. You get $1000 if you beat the champion in three minutes, $1000. What you had to do was sign a hold-harmless agreement, saying that if anything happened in the ring, we’re not liable for it in any way, shape or form. Then have it notarized and witnessed. Second, you had to put up $250 as an entrance fee. We used to go around to all these logging camps with all these big loggers who thought they were tough, and have them challenge Dale. Dale never lost that thousand dollars.”

Though he may not have been a major box-office star, Lewis had his share of friends and certainly made an impact on the business.

His best-known ‘protege’ was Gene Petit, and they met at the apartment complex in Florida where many of the wrestlers lived. Petit was a University of Florida football player and became friends with Dale through Dale’s daughter Kimberly. He progressed to driving Dale to the matches and later learned the ropes himself and became Dale’s tag team partner and ‘brother’ as Gene Lewis.

In his Whatever Happened to … interview, Petit talked about Dale’s reputation and his standing with the fans. “Dale was in a program with Jack Brisco, which is Oklahoma versus Oklahoma State, and Dale was a heel. I’ll never forget one match at Fort Homer Hesterley Armory (in Tampa) when Dale wrestled Jack for the (Florida Heavyweight) title. They had a sell-out. They must have wrestled forty-five or fifty minutes, and Dale never heeled. He wrestled clean, broke clean, and was actually getting cheers from the people. They finally did a move where Dale rolled Brisco up. The referee counted “One, two,” and Dale held Brisco’s trunks to get the three count. There was a riot, but at first … you could hear a pin drop. I mean, they had great respect for Dale’s wrestling ability. Dale hadn’t heeled all night, they had this great scientific match, and they did one tiny deal to end it. Can you imagine pulling the tights for a finish? What psychology they used. It caused a riot and it was an hour before Dale was able to get out of the building.”

Brisco helped Lewis out. “We developed a version of the chicken wing, where he would lock it in and hold you over his back, for him to use as a finisher,” he wrote in his book. “We called it the ‘Lewis Lock’ and he carved a path of carnage and destruction throughout the state, leaving each and every opponent conceding and injured. We played him up as hell on wheels and his ‘Lewis Lock’ as being invincible.”

When Watts started in pro wrestling, he was sent up to Indianapolis where he also played semi-pro football. Watts lived with a coach from the team and Dale Lewis. “Dale came and worked out with me, gave me my workout gear. That’s when I really got to know Dale better, even though we’d been college teammates. I really got to know him as a person. Dale had a heart of gold. I got to know his family in Milwaukee, spent time there.”

Watts had his first pro match against Dale Lewis. “That was another complete accident. I used to go to the matches each evening. I was playing on the football team, working out and going to the matches. Art Neilson, who was a big star, called me and he said, ‘Take your bag because it’s clear down to Portsmouth, Ohio, and I’m not going down there. It’s not going to pay worth a dang, and I’m not going. So take your bag and they’ll have to use you.’ Then about five minutes later, I get a call from Art’s tag partner, Stan Neilson, who stuttered real badly but was a neat, neat guy. ‘T-t-t-t-ake y-y-y-our b-b-b-a-g, I’m not going to show up and you’ll t-t-t-ake my place tonight.’ So I knew I was going to wrestle. I got down there and they wanted to change the match and put me in the main event with Dr. Bill Miller, who I’d met and was really impressed with. He liked me too, but I was scared to death I’d screw it up since it was first match. So they put Don Jardine up against Bill Miller. They put me with Dale. Dale said, ‘Well, you know you’re going to have to put me over.’ I said, ‘Hell, I put you over in college. At least I get paid for it here.’ We went out and worked. I worked heel. I’d never worked heel. I mean, I never had a match. I just had that natural thing, and we had the people going crazy. When he said it’s time to go home, I’d get the heat, when I hit him, I knocked one of his teeth out! He said, ‘Gosh, damn, I give you your tights, I work out with you, everything else. And how do you pay me back? You knock my tooth out!’ I said, ‘Well, you deserve it. You’re an asshole.’ There was great camaraderie.”

Life on the road separated Watts and Lewis. “We never got to a point where we spent an awful lot of time together, just because of the way my career went and his career went. He sure benefited my life.”

After Lewis got out of wrestling, he managed an RV and motorhome dealership in the Pacific Northwest. He died August 30, 1997 of leukemia at the hospital of the University of Oklahoma. He was 62.