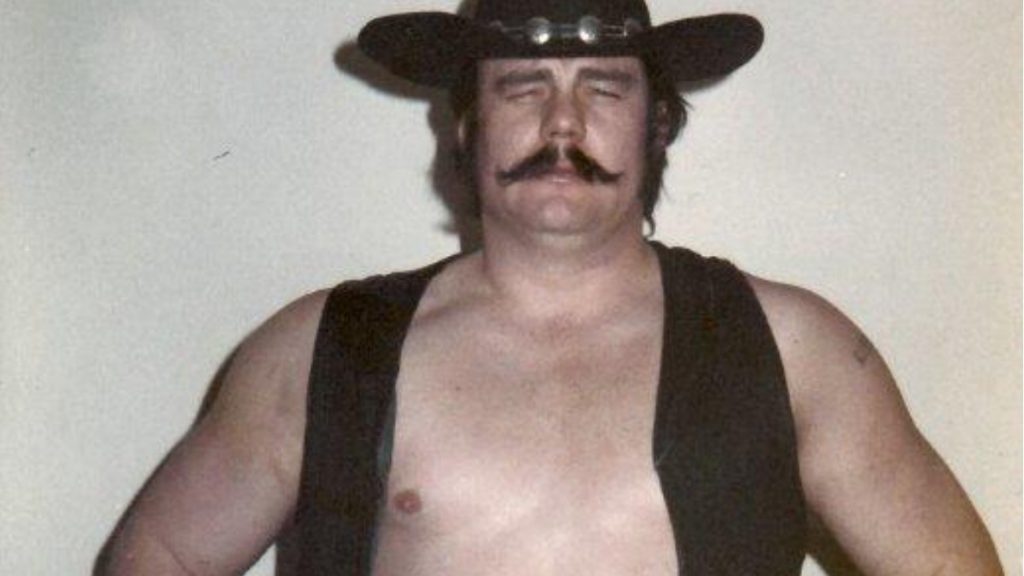

Blackjack Mulligan, in 1986, during his WWF days.

As a junior in college at West Texas State, Barry Windham appeared to be headed for the NFL. He had the talent and the lineage, as his father Jack Windham had also made the NFL with the New York Jets before becoming a pro wrestler.

But it wasn’t to be for Barry. He dropped out of school to follow his father into pro wrestling. While the youngster would prove to be a star in the business, his father was hurt by his decision to leave school.

“He said, ‘Dad, this is not what I want to do.’ It really just crushed me because I really wanted him to go finish school,” explained the senior Windham, better known to fans as Blackjack Mulligan.

While Mulligan was on a trip to Japan, his business partner in the Amarillo, Texas area, Dick Murdoch, let Barry referee a few matches and help set up the ring. Then one day, a wrestler was unable to perform and the kid stepped into the ring for the first time.

“Barry knew all the moves. He’d been learning it from birth,” explained Mulligan. “It’s kind of a heredity thing. He never himself, per se, trained, because he was there all the time anyways. I guess it’s inbred genetically. He knew all the moves. From his first match, he was a success.”

For the Hennig family, there was also a tradition of wrestling. Larry ‘The Axe’ was a major star in the American midwest, and it seemed logical that at least one of his children would follow him into the squared circle. “In our family … it was a tradition. Everybody wrestled,” recalled Hennig.

His son Curt did enter pro wrestling. “[Curt] took a good, long look at it and decided if he wanted to pay the price, the sacrifices, and that he’d do it. He certainly did it. He was always a great athlete,” said the elder Hennig. He sent his son to train with former U.S. Olympian Brad Rheingans. Soon, father and son made up a formidable tag team combination, a paired that the father called the highlight of his career. Later, Curt became a major star in the WWF as Mr. Perfect.

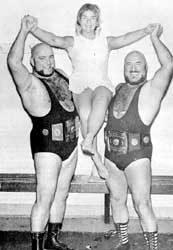

Paul, Vivien and Maurice Vachon.

For Paul ‘Butcher’ Vachon it was a totally different matter. It was his daughter Angelle that wanted to become a wrestler. “I thought it was the worst business a woman could be in. It’s not even a business for men,” Vachon explained. Yet he also knew that it was part of the family legacy, with his brother Maurice ‘Mad Dog’ Vachon and sister Vivien Vachon having extremely successful grappling careers.

“She could have done anything. She was a beautiful girl and very intelligent, smart, good looking, of course, like her dad,” joked Vachon. “All she ever wanted to do [was wrestle]. Her idol was my sister, Vivien, who was a wrestler. She had been watching her ever since she was four or five years old. That’s all she ever did. I told her she was a lunatic because all she wanted to do was wrestle.” Years later, Angelle Vachon became ‘Luna’ Vachon, a successful pro in the ring, winning many titles and freaking out many people with her bizarre mannerisms and dress.

Father and daughter used to work out together in the rings of the World Wide Wrestling Federation throughout New England. “We’d go early and get there late afternoon, the building would be open and the ring was up and no people in the place,” recalled Vachon of the days training his 14-year-old daughter. “We’d get up in the ring and I’d show her a few moves. Then some of the guys would start coming in and they’d help me start putting her through some paces.”

Vachon, conceding defeat, got his daughter booked for some matches in Japan, and even went along as her manager. “I expected her to be a success but I was hoping she wouldn’t be, to tell you the truth.”

Luna Vachon.

Sometimes, the father doesn’t even know that his son is a wrestler. Angel Acevedo is best known to wrestling fans as the Cuban Assassin. One day, out of the blue, he got some photos of his son Richie from his first marriage in the ring. It surprised him because he knew that his son was into karate, but didn’t know that he wrestled as well. In the summer of 1999, father and son teamed up on the Grand Prix circuit in the Maritimes.

With his second son, Kendall Windham who is 10 years Barry’s junior, Blackjack Mulligan did things differently. “Because of the experience I had with Barry, I said to Kendall that ‘I want you to at least complete two years of vocational school or some kind of training so that you’ll know a trade if this don’t work out, because the business is changing. I want you to have a trade, a skill.”

Years ago, the pro wrestling business was different than today. Wrestlers moved from territory to territory. Some stayed a short while, some stayed for years. Some wrestlers left their families in one city while they went out on the road for months at a time. Others, like the Windham family, travelled as a unit.

“I always took my family with me. It was very difficult. At first, I thought I was like a carnival worker,” recalled Mulligan. “We stuck with the Lutheran schools because the levels were kind of the same. We knew we were going to make a move a year ahead, and moved every year, sometimes twice in one year.

“They saw me very little, but I had a very good wife to raise my family into a real solid family.”

Mulligan kept his children in the private Lutheran schools until grade 10, when it was time to go to the public schools — primarily because the football systems were better. He was an education major at West Texas State, and knew that there were certain ages where his children should be grounded. “[Grades] one to three they needed to stay. Then past seven, they started making social contacts, they needed to stay. Then in high school, we needed to stay. So there’s certain areas in their life that I kind of controlled.”

Initially, “it was hard on the family,” especially when the Texans moved north to Minneapolis and the Dakotas to wrestle for Verne Gagne’s AWA. According to Mulligan, it was a real “cultural shock.”

Mulligan also found another problem with being on the road. “You’re gone on the road so long, all these little disciplinary problems have built up. After a while, you become the disciplinarian. The only time they see you is when you’ve got something bad to say to them.”

It’s probably partly for that reason that other people ended up training his sons for their career in pro wrestling. “It’s very hard [to train your son] … because you’re so hard on the kid. It’s better to let a third party train. And when there’s third-party people like Jack Brisco and the Kiniskis around, they probably know more than I do. They spend time with them in the ring. … Probably a third of their introductory learning level they learned from me. The two-thirds, they learned from somebody else. It’s very hard to be your son’s coach because you’re the disciplinarian.”

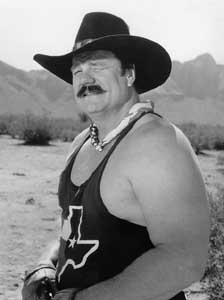

Larry Hennig

Larry Hennig was able to act as a colleague for his son Curt as he set out on the road on his own. “I had the road map. I had been there. Decisions were probably a lot easier for him to make because he always had somebody to bounce something off of.”

Bob Orton Jr. knows all about life on the road. His late father, Bob Orton Sr. was a successful wrestler before he got into wrestling. And then Junior followed Dad into wrestling, starting as a referee until bulking up and increasing his size. Now, Orton Jr.’s 20-year-old son Randy is ready for the next step.

Orton knows it was tough on him to have a father away all the time, just as it was difficult on his own children. “I didn’t really know my dad until I was probably out of school. It’s tough. You’ve got to take care of yourself a lot. Of course, my mom was great. You know, it’s just the way life is. You’ve got to go with what you’re dealt.”

For his son Randy, Orton has tried to lay out a sound foundation before he gets into wrestling full-time. “What I’ve done is shown him how to wrestle, to do the things like I did, even though that’s probably passe now. But still, it’s a good sound base.”

“You always want your sons to do better things,” summed up Mulligan, whose his son Barry eclipsed anything he ever did in the ring, but his son Kendall never really hit it big. But he also thinks that the comparisons of yesterday to today are inherently flawed. “We probably wouldn’t survive in this atmosphere, and they probably couldn’t survive in our atmosphere.”

RELATED LINKS