Without Verne Gagne, pro wrestling wouldn’t be the multi-million dollar industry that it is today.

If somehow you were able to alter the time-space continuum, and take Gagne out of wrestling to prove that statement, there would be some huge voids. For one, the American Wrestling Association probably would never have formed in 1960. Who would have trained future world champs like Ric Flair, Ricky Steamboat, the Iron Sheik, Bob Backlund, Curt Hennig for the sport? Without the seasoning and national exposure that Hulk Hogan and the Road Warriors got in the AWA, would any of them changed the wrestling business the way they did?

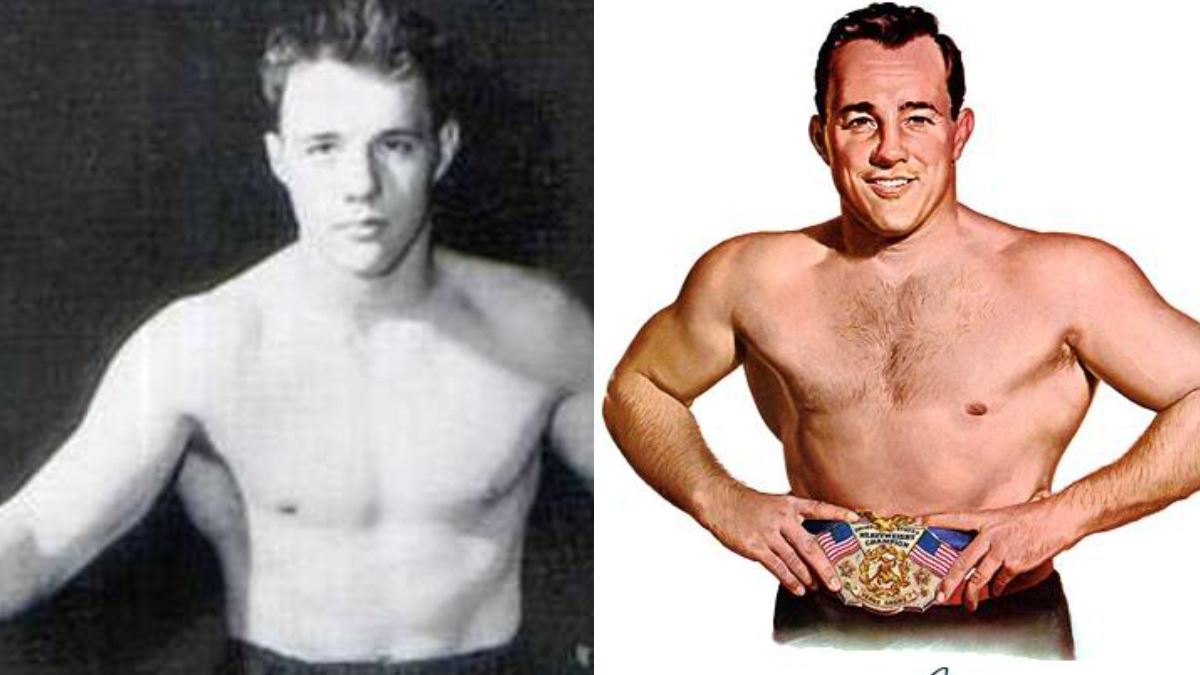

Verne Gagne, circa 1970. (Courtesy Verne Gagne.)

At its peak, the AWA ran from its Minnesota base all the way from Chicago to Winnipeg, straight through Omaha, Denver, Salt Lake City, Las Vegas to San Francisco. It was a massive territory, dwarfing the northeast-based WWWF. Ratings were huge, sometimes beating the Vikings and Twins in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis-St. Paul. Yet, because it’s not around any more — Gagne having thrown in the towel in the early ’90s — the promotion probably doesn’t get the credit it deserves.

Today, nine years after getting out of the wrestling business, does the 10-time AWA world champion Gagne miss being involved? “It was fun. I liked it, enjoyed it, but I can’t say that I really miss it,” Gagne told SLAM! Wrestling recently. “I was doing everything at one time — wrestling and promoting and match-making and all that.”

Gagne spends his time doing fundraising for the U.S. Olympic wrestling team, and the team at the University of Minnesota. “I’m involved in a lot of things. It keeps me busy. I like it that way better than just sitting and laying around. I play tennis a lot. I’ve got a couple of other businesses going on the side here.”

A successful amateur wrestler himself, who competed for both the University of Minnesota and 1948 Olympic teams, Gagne made his professional debut in 1949 against Abe Kashey. He was a successful light-heavyweight — including a stint as the NWA Jr. champion — before getting his break and appearing on the old Dumont Network’s weekly wrestling show out of Chicago.

In 1959, some members of the National Wrestling Alliance got fed up with Lou Thesz as the world champion, and recognized Edouard Carpentier as the champ after Thesz was disqualified in a match. In 1960, Gagne beat Carpentier to become the first champion of the newly-established AWA. Gagne held the title 10 times over his 35-year career, his last reign starting in 1980, and ending in May 1981 when he retired (though a couple more matches did follow).

Besides the aforementioned world champions, Gagne was also responsible for training other stars like his son Greg, Larry Hennig, Baron Von Raschke, Jim Brunzell, Ken Patera, Brad Rheingans, Sgt. Slaughter, Buddy Rose, the Steiners, Buck Zumhoff.

Needless to say, given his own amateur wrestling background, Gagne doesn’t think too much of today’s wrestlers, except maybe Kurt Angle.

“There’s no wrestlers in wrestling,” said Gagne. “There used to be a thousand-I-don’t-know-how-many wrestlers out there. There were 26 booking offices at one time in America and everybody had a job. Now there’s only two big companies, and that’s it.”

The openness of wrestling today, where the wrestlers will talk about how everything is pre-determined and a big show, doesn’t bother Gagne as much as the lack of defined rules. “I don’t know what the rules are in wrestling today. We had certain rules — over the top rope was a disqualification, if you threw someone over the top rope, if you ran them into a ring post, you were out of there. Now they bring in tables, chairs, and slam them on there. And they let it go. There’s nothing that makes it a sport of any sort. … It’s kind of pathetic. But it’s getting ratings, and it’s selling merchandise so what are you going to do?”

Looking back on how hot the AWA was in the early ’80s, Gagne knows that the company missed some opportunities. “The thing we didn’t take advantage of a lot was merchandising, which is huge now. We decided to sell some of our programming overseas to a few different countries. But other than that, the crowds and of course, the prices, then are not what they are today,” he said laughing. “So they’re grossing a lot more, whether they’re making any more money, I don’t know. Everything has gone up.”

In 1985, to combat Vince McMahon’s expansion plans with the WWF, Gagne teamed with the main NWA promoter Jim Crockett Jr. to create Pro Wrestling USA. They put on a couple of mega-cards, true inter-promotional dream shows in McMahon’s backyard at the Meadowlands in New Jersey. For example, the second Night of Champions on December 25, 1985 saw Stan Hansen beat Rick Martel for the AWA title, Ric Flair defend the NWA title successfully against Dusty Rhodes, plus appearances by the Road Warriors, Magnum T.A., Tully Blanchard, Sgt. Slaughter, Carlos Colon, the Rock’n’Roll Express and more.

Could the Crockett and Gagne have competed with McMahon if the alliance held together? “Oh, well, I don’t know,” offered Gagne. “Vince, we had him on the ropes there pretty good, but he got an influx of money from someplace and was able to survive and went on from there. Probably, probably. It was hard to organize everybody.”

The WWF’s expansion in 1983-84 saw them raid the AWA for a massive amount of talent, most notably (at the time) Hulk Hogan, Dr. D. David Shultz and announcer Mean Gene Okerlund.

Gagne recalled Hogan’s early years for SLAM! Wrestling. The soon-to-be Hulkster had had moderate success up until this point, about 1982.

“When he called me, I didn’t know who he was,” said Gagne. “He called from Tampa. … I said, ‘Look, who are you?’ He said, ‘I’m Hulk Hogan.’ Greg happened to be in my office. I said to him, ‘Greg, have you ever heard of a guy by the name Hulk Hogan?’ And he said, ‘Yeah, I saw him in New York one time.’ I said, ‘How was he?’ He said, ‘Ah, so-so.’ He said, ‘He’s a big guy.’ So I said ‘Okay.’ Then I’m back talking to Hogan. He said, ‘I’d like to give it one more try. I’ve quit wrestling ’cause I can’t make it. But I’d like to give it one more shot. I’ve been sitting here for the last three, four weeks or a month, and could I come into the AWA?’ So we brought him up, and the rest is history.”

The Hulk Hogan that became the international celebrity was developed in the AWA. Watching old tapes proves it beyond a shadow of a doubt — the same catch-phrases are there, the ring actions, the unbelievable fan reactions. “There was a lot of work turning him around into a Hulk Hogan that meant something,” said Gagne.

Looking back on those days now, Gagne can recognize how the business was changing. Partly, that was because of the arrival of steroids.

“I first heard of steroids, I think, in the ’70s,” Gagne said. “When they first came out, the guys didn’t know that they could hurt them. We had some guys die, overtake, take too much, or whatever. When that starting going, it seemed that the quality of the wrestlers changed.”

He said the AWA tried to hold out as best they could against the changing physiques and match styles. “We kind of held the line on what was wrestling, and what wasn’t wrestling. We had some matches that were a little bit unique – cage matches, battle royales, and you name it …. Most of the guys are on steroids today and they’ve got the big bodies, the muscular bodies that look good. But as far as watching the matches, the ones I see, are kind of a routine type thing. You hit me, and I’ll hit you. We’re [not] going to hurt each other, we’re just going look like we’re hitting each other.”

The other change that bothers Gagne is the lack of true good guys and bad guys. “The good guys were the heroes in our era, and the bad guys were not. Now what you’ve got are the bad guys as the heroes. It has an affect on society, I don’t care what anybody says,” explained Gagne. “I know just from the things that they do in the ring — the gestures, the interviews, the terminology, the words — the kids pick up on it. And I don’t think that it’s a good influence.”

Yet he will admit that hooking the kids is the key to a successful promotion. “Kids love wrestling and they’ve always been a big part. I know with our ratings that if we could get the kids, then the parents. And once they start watching, they’re into it also.”

Gagne’s Canadian Connection

Having heard about SLAM! Wrestling’s Canadian Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame, the former U.S. Olympian Verne Gagne made his pitch to being inducted.

“My forefathers are from Canada, from Quebec,” he explained. His ancestors came from France in 1646 to Ste. Anne-de-Beaupre, and stayed there for 200 years before heading to Minneapolis in 1954.

He even visited the small town once with Mad Dog Vachon. “There’s church there, little church still there, still standing, a brick church. A cornerstone says Pierre and Rose Gagne built the church on this site.”

RELATED LINK