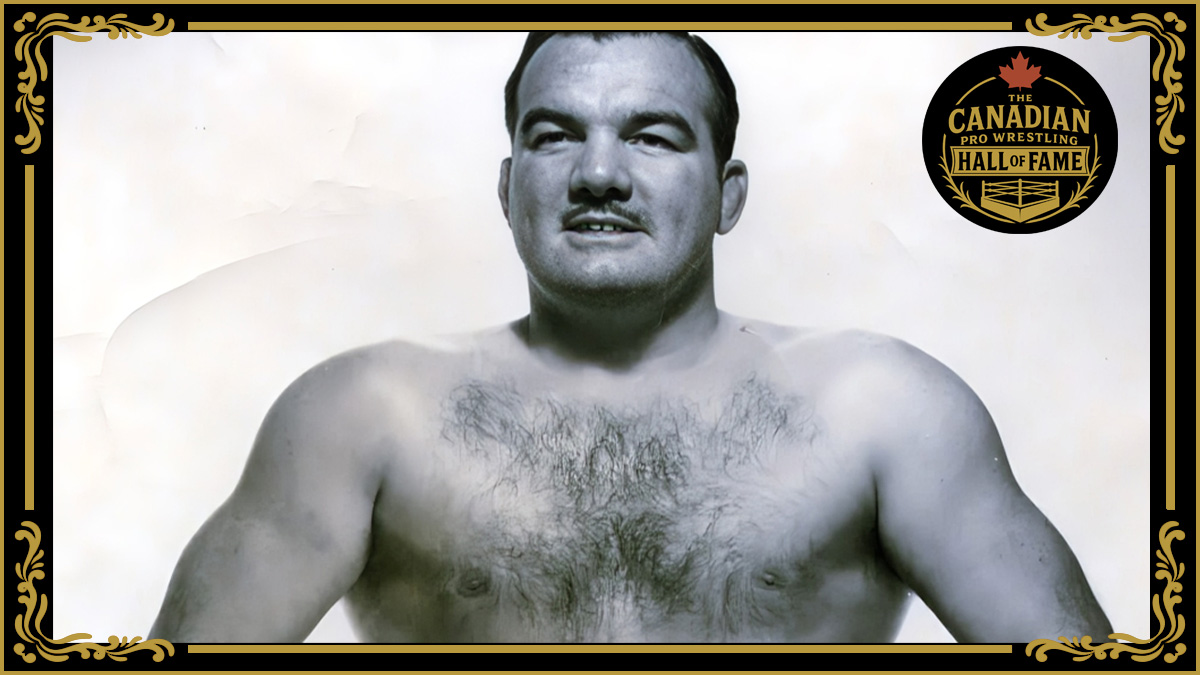

It’s been 10 years since we lost The Whip to a heart attack.

But how does one explain the appeal, the legacy of Toronto’s William Potts, aka Whipper Billy Watson, to today’s wrestling fan?

Well, by talking to a few fellow wrestlers who knew him, inside and outside the squared circle.

“The thing that I remember about Watson was that every time you beat him, you had to fight your way out of the ring!” explained Don Leo Jonathan, laughing at the recollection. Such was the fervor that Watson inspired in the faithful of Southern Ontario and Western New York.

Watson began his wrestling career in 1936 in England, and it lasted until 1971 when an automobile accident forced him from the ring, and into tirelessly working with charitable organizations on a full-time basis. The Whip knew no shame in using his celebrity to further the causes of the right and the just.

In the ring, Watson was the one dealing out the justice. Always the fan favourite, he virtually controlled the Toronto promotion owned by Frank Tunney.

“He was the boss, so if you didn’t do exactly what he wanted, he would go back to the office,” recalled Hans Schmidt, one of those famous goose-stepping German heels of the post-World War II era.

“When you go in the ring with him — I’ve wrestled him about 1,000 times — it would have to be his own way, otherwise, [laughing] things would stink a little bit,” added Schmidt. “If you don’t do like he says, like he wants, he might not talk to you for a week.”

Gene Kiniski was another of those killer heels that made Whipper all the more famous for fighting off his evil ways.

“I wrestled him so many, many times. I think I wrestled him in every city and village in Canada,” said Kiniski. “In fact, the first time we met in Newfoundland, my God, you couldn’t get near the airport. They had the largest crowd in the history of Newfoundland to welcome him.”

Kiniski knew his role. “When I wrestled him, people went in there to see me beat. And I’d just go out — I had a flamboyant style. I’d just give them action, action, action because I’m a rough, tough son-of-a-gun. And as a result, we just drew so much money.” Throughout the matches, it was Watson in control. “He was coaching, and I was doing all the offensive work.”

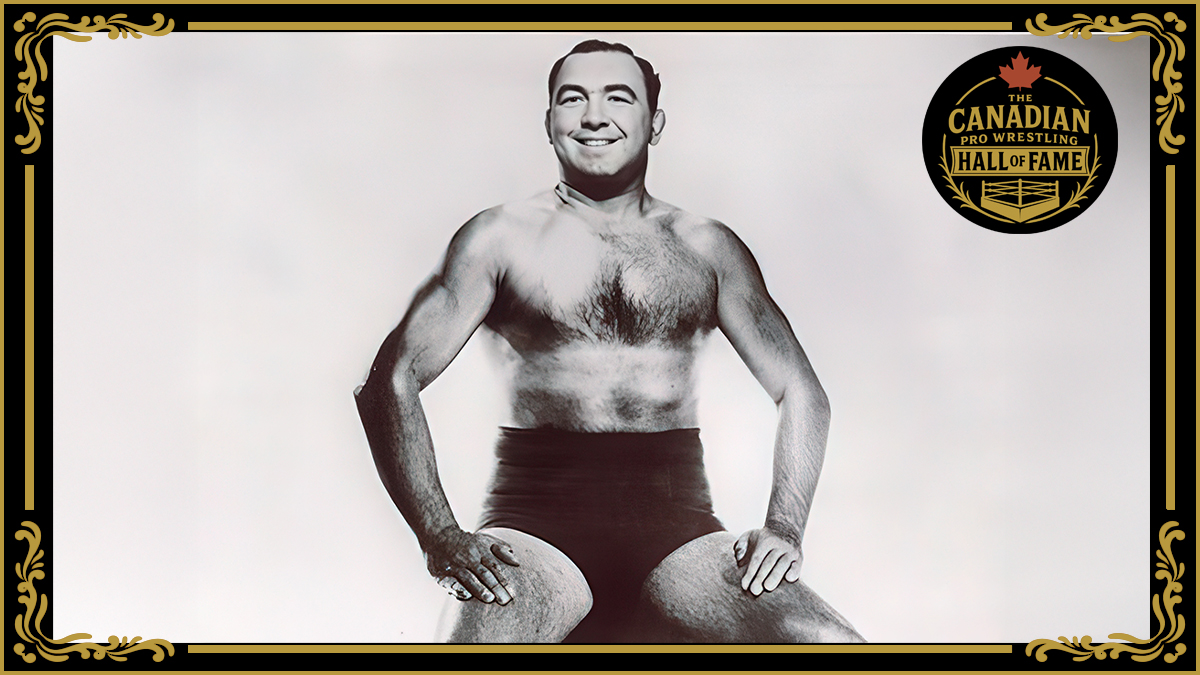

Lou Thesz beat Watson for the NWA World title to Watson on two separate occasions. The first time was on April 25 in Indianapolis (after Whipper had beaten defeats “Wild” Bill Longson in St. Louis on February 21, 1947). Thesz lost the title to Watson on March 15, 1956 in Toronto via a count out, and won it back November 9 of that same year in St. Louis. Altogether, Thesz figured that he only fought Watson a half dozen times though. He agreed with the assessment that Watson wanted his way in the ring, but Thesz said that to counter that, he just out-wrestled him.

Despite his lack of praise for Watson’s in-ring ability, Thesz did recognize the importance of both Watson and his French Canadian equivalent Yvon Robert, and the role they played in the lives of their fans. “[Watson and Robert] were both promoted very well, and really, really did a great job. They had a great deal of visibility, and they did well. And both of them drew a lot of money for the promoters, and did very, very well.”

The Mormon Giant Don Leo Jonathan, as an American living in Canada, heard a lot of griping about Watson’s title reign. “That time when he had the championship, there was a lot of guys that didn’t figure that he should have it. And they were out to get it. And they was hitting on him pretty hard. ‘What is a Canadian doing with the world championship anyway?’ You know, that’s the attitude,” Jonathan explained. “Nobody liked it even when [Yvon] Robert had the championship. There’s a lot of good wrestlers in the States, and that was sort of an affront to them. It’s like the Stanley Cup going to New Jersey.”

Whipper Watson also had an impact on many of the younger wrestlers, some of whom were just breaking in as his career was winding down.

Paul Leduc was Watson’s partner for one match in Cornwall, Ontario in 1965. “It was a big, big, big souvenir for me,” he said.

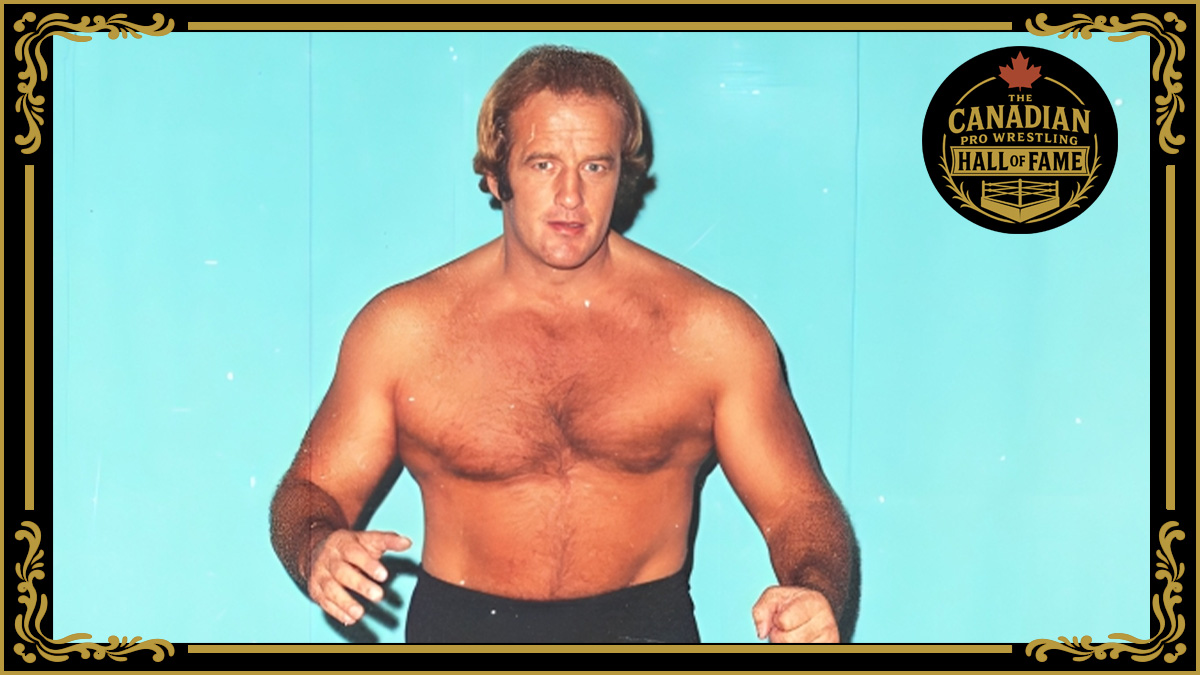

Ronnie Garvin wrestled Watson at the end of his career, the beginning of his own. Garvin remembered being in awe of The Whip. “He was the big star and I was just starting,” Garvin said.

Of course, all of this merely takes into account Watson the wrestler, not Watson the man, Watson the community leader, Watson the champion of charity.

“He was just a phenomenal individual,” said Kiniski. “I can’t, to be honest, speak highly enough for him, about him.”

“He was a great, great asset to the world of professional sports. He was known worldwide, and of course his name Whipper Billy Watson was synonymous with wrestling in Canada.”