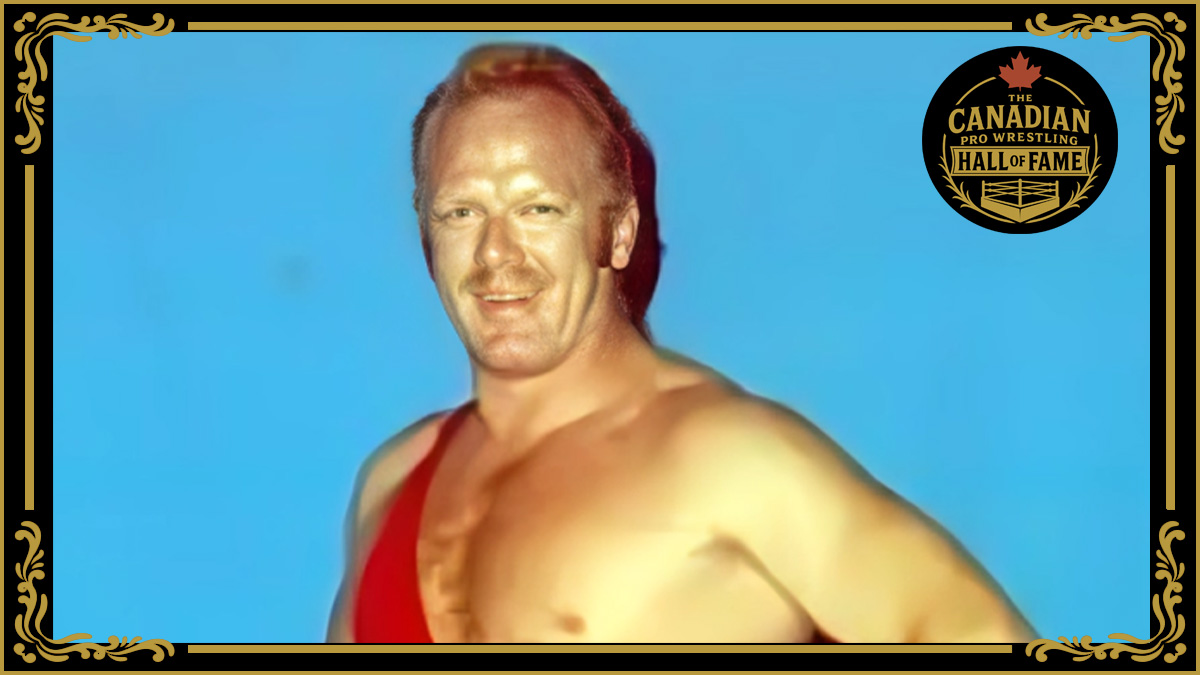

REAL NAME: Louis Gino Acocella

BORN: May 18, 1941 in Montreal

5’10 1/2 “, 240-245 pounds

AKA: Louis Cerdan, Gino Brito

You can’t talk about Gino Brito without talking about his long-time partner Tony Parisi and the midgets.

Despite excelling in both wrestling and promoting, Brito’s career owes much of its success to the half-size stars of yesterday like Sky Low Low, Little Beaver and Fuzzy Cupid and to his good friend Tony Parisi.

His father, Jack Britton, was the promoter in Montreal and the man behind the midgets in the 1950s. Britton had two dozen midgets in his stable at one point, and his son’s job was to travel the roads with them, shuttling them from town to town, promotion to promotion.

“I had the fortune of travelling with the midgets all over the country,” Brito told SLAM! Wrestling from his Montreal home. “So one night, I would go in with Vince McMahon in New York, wrestle for him there, then go with the midgets somewhere else, to Minneapolis to wrestle there. So I got the promoters to know me. When I started finally to wrestle on my own, well then it was easy for me to pick up the phone. They knew me.”

As for Parisi, Brito’s first big break came with ‘Cannonball’ Parisi while working Nick Gulas in Nashville, Tennessee. “Within two weeks there, we had the belts. That was really the start there. After that I went to Georgia, I did all the territories.”

The promoters not only knew Brito, but they knew his father, who wrestled around Montreal beginning at only 16 years of age. And then there was his uncle, who was best known around the Boston area as Lou Kelly. Later, Brito’s son Gino Brito Jr. followed in the family business for a short career as a grappler.

“I was around wrestlers all my life,” explained Brito, who wrestled as an amateur before starting training to be a pro at 17 and a half years of age with George McArthur (George Cannon). A year and a half later, he broke in with the Detroit promotion run by Bert Ruby and Harry Light, who had business dealings with his father.

For his first few matches, Brito remembered hitting small towns like Chatham, Ontario, “where you made 12 bucks for a match.”

“It was the first or second match, but I was picking up a payoff,” Brito said. “I was working, picking up experience, plus getting known. The promoters, they liked what they saw.”

Over the years, Brito used many different names, some only for a show or two. But Montreal’s Louis Gino Acocella was best known as Louis Cerdan and later as Gino Brito. He recalled how he got the name Brito. “For me, it was simple. I took the name Britton, which was my father’s, and I took off the end. People around here (Montreal) knew I was from Italian descent and all that. I made it into Gino Brito.”

That Italian descent was both good and bad during his career. During his first time through New York, he was the French-Canadian Louis Cerdan (his first name, and Cerdan was an old-time boxer) “to stand out a bit” from all the Italians in the WWWF at the time — Ilio DiPaolo, Dominic Denucci, Tony Parisi, Bruno Sammartino, Lou Albano, Tony Altamore. “It looked like Little Italy there,” Brito remembered.

The days in the WWWF included a run as tag team champions with his best friend Tony Parisi. Cerdan and Parisi beat the imposing duo of Blackjack Lanza & Blackjack Mulligan for the tag titles in 1975, and lost to the Executioners in 1976.

“We had a good run there in New York,” he said. “It was the best money that I ever made in wrestling.”

His Italian friends had a lot to do with the fun he had there. “We had a little clique between Sammartino, Denucci, myself and Parisi. Once in a while, Tony Marino, another Italian, would come down. … I enjoyed being around there. Plus, it was close to home. I would come home every weekend and the money was good. Let’s face it. The population there is so dense. You’d sell out New York’s Madison Square Gardens, Philadelphia at the Spectrum or the old Market Arena, the Boston Garden. It was a helluva good run there.”

When he wrestled as Gino Brito, he could let his Italian fire out. It made an impression.

“What I admired about [Brito] was his fire. The fire in his style, very aggressive, very explosive wrestler,” explained former AWA World champion Rick Martel. “I remember when I was a kid, I was 10 years old, I’d go to wrestling and he was one of my favourites. I remember when he would explode, he would just go crazy. I admired to explosive style he had. So when I got to be around him, I liked that.”

According to Brito, it was Abdullah the Butcher that brought out the fire best in him. “Somehow that match clicked, because we went all over. We drew some good crowds all over. I think I got the best out of Abdullah The Butcher and he got the best out of me.”

The move into promoting in 1980 was a natural one, even if it was sped along by the death of his father that year. Wrestling in Montreal was pretty stagnant in the late 1970s, following the boom of the Vachon-run Grand Prix Wrestling and the Rougeau-run International Wrestling in the early ’70s. Jack Britton started running again in 1977 without TV. Three years later, his son finally secured a TV deal in Sherbrooke, which led to a renaissance in pro wrestling in Montreal.

“All of a sudden, the territory popped,” Brito said. “We got channel 12 in Montreal, and we had TV covering all of northern Ontario. We went as far as Thunder Bay, Ontario to the Maritimes.”

At various times, Andre the Giant, Dino Bravo and Tony Muley were partners in the International Wrestling promotion.

“The first big sellout I had at the Paul Sauve Arena, where the firemen came in and closed it down because we had too many people in the building, was when I had Hulk Hogan against Jean Ferre (Andre The Giant) at the Paul Sauve Arena,” Brito recalled of a big year in 1983, that also saw Bravo battle the Masked Superstar (Bill Eadie) across the circuit.Brito remembered some great feuds and matches from his days as a promoter. The Rougeaus, Rick Martel, and Bravo were great, young French-Canadian stars that drew the fans in, but it was the veterans like Billy Robinson, The Destroyer, Abdullah the Butcher and Masked Superstar that made the territory. Rounding out the cards were names like Pierre ‘Mad Dog’ Lefebvre, Sheik Ali (Stephen Petitpas), Michel ‘Le Justice’ Dubois, Tony Parisi, Neil ‘The Hangman’ Guay, Gilles Poisson, Mad Dog Vachon, Richard Charland, Louis ‘The Farmer’ Laurence, and Sailor White.

When Vince McMahon Jr.’s World Wrestling Federation was starting to ramp up in the mid-’80s, Brito lost the Rougeaus and Bravo to the competition, and Rick Martel had gone to the AWA. He made the mistake that all of the other regional promoters did — he tried to fight the WWF. “We ended up losing because we didn’t have the machine behind us and the money.”

After Bravo and Rougeaus left, Brito ran for about another nine months. “That was a big, big mistake. That’s where I lost a lot, well, everything that I had made so far. I dropped everything in that promotion. It didn’t take long when you’ve got TV and it’s costing you, even in those days, $8,000 a week to keep things going. And you’re already losing money, plus on top of that $8,000 a week. You can imagine, I did that for seven and a half months before everything went bankrupt,” Brito explained about closing down in 1987.

“I took the fall there and lost close to half a million bucks in the promotion.”

Raymond Rougeau remembered how tough the decision was to leave Brito and International Wrestling. “I liked Gino. Gino was a good guy. I always got along good very well with him. But it was a career move. Anyone would have done the same. I left in a very civilized way. I didn’t just say, ‘Bye Gino, I’m gone! I’ve got a contract with the WWF.’ I even told Vince, I said, ‘Vince, I want to give them a good notice so they have time to get somebody else, to re-organize.’ And Vince agreed 100 per cent. So when I came back, first thing I did when I landed in Montreal, I went to Gino’s house and I explained it to him. ‘Gino, you have to understand, this is a career move.’ He said, ‘No, on a selfish basis, I’d say no, I don’t want you to go.’ But he says, ‘On an objective basis, you have no choice. That’s the thing to do.’ Gino and I always stayed on good terms with that. Dino Bravo took it a little harder. He didn’t talk to us for a while.”

After throwing in the towel, Brito was asked by long-time friend, and fellow Montrealer, Pat Patterson to be the promoter for the WWF in Montreal. He knew that he wasn’t really needed, that the WWF hype and promotional machine was enough to draw good crowds in Montreal, but he stuck with it for four years because wrestling was the only business he had ever known.

“My life was wrestling. All my life. I wrestled 25 years as a pro, then I promoted another 10 years. It was hard getting out of it, but there was nothing there for me anymore,” Brito said. “I tried a few local, little promotions after that. Every promotion I would drop two, three grand because you weren’t drawing 300, 400 people.”

Today, he works with his brother-in-law in the car business. Brito is more into buying and the auction end of the business than the sales side. “I find it a little slow. You’re days without doing much. But it’s a living and it’s not a bad living. We’re doing okay. We’re the biggest Subaru franchise in all of Canada.”

TRAVELLING WITH THE MIDGETS

The midgets have always made crowds laughed. Yet, from hearing Brito describe it, they were exactly a joy to shuttle around.

“That was a job in itself. You had to have a lot of patience. I was young and I didn’t,” he recalled.

Brito took around different groups of midgets at different times. Some of the bigger names included Sky Low Low, Little Beaver, Fuzzy Cupid, Irish Jackie, Cowboy Cassidy, Farmer Pete, and Pee Wee James.

It’s Sky Low Low, the greatest of the little ones, that brings out the best stories.

Brito would have to take four midgets and their wrestling gear from a downtown New York City hotel to Philadelphia for TV in the afternoon. Only Sky Low Low can’t be found.

“You’re looking for him and he’s out with some broad somewhere and you can’t find him. And you’re responsible for him. All of a sudden, you spot him and you’ve got one hour to go from New York to Philadelphia, which you’re going to be late anyways. He says, ‘She’s coming with me! I’m marrying her.’ The broad, the next day, she made him for $700.”

One story leads to another once Brito gets going on his experiences.

“Every day, my dad used to tell me, you give them an advance, $100 a day advance, which was a lot of money back in 1960. They’re paid just the advance. Most of the time, they’d come back, like two in the morning, I’d be sleeping. Let’s say we’re in New York, and he’d be at the Copacabana with Dr. Jerry Graham. He’d come knock on my door and say, ‘I need a couple of hundred bucks more.’ But the money they made! A guy like Sky Low Low was making like $1,500 a week, sometimes more, which was big money at the time.”