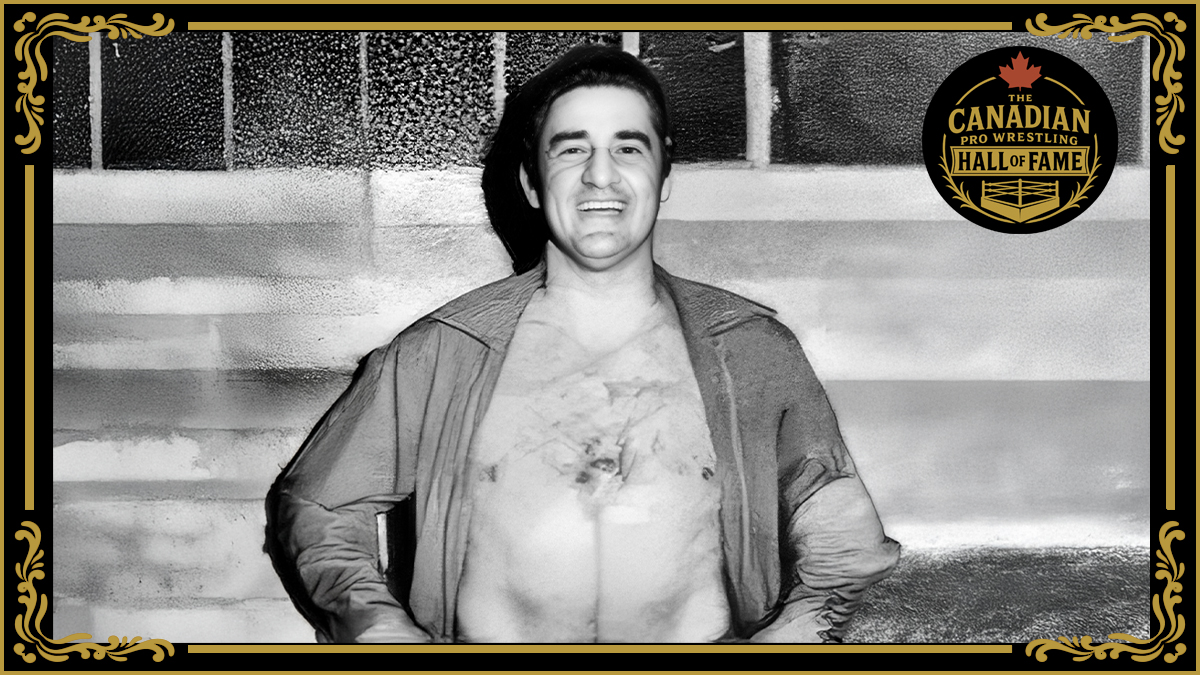

REAL NAME: Carl Donald Bell

BORN: Kahnawake, Quebec

6’2″, 222 pounds

DIED: March 17, 1966 at 41 died of a gunshot wound

Don Eagle, a Mohawk from the Kahnawake reserve in Quebec, deserves recognition as one of the greatest box office attractions of the early days of televised wrestling. For a time, he even rose to become one of the regional world champions.

But that only tells part of the tale of Don Eagle. To friends and colleagues, he was a complicated man that brought the Indian way of life to the white man.

“I think the main thing with him, besides the fact that he was a good wrestler, a scientific wrestler, [was that] he gave the white people, or the rest of Canada, a better look at what the native people were like,” explained Don Leo Jonathan to SLAM! Wrestling. “[Nowadays] First Nations peoples stand different in the eyes of their fellow Canadians than they did 40 years ago. It was a slow process, but one that I think Don Eagle sped up.”

No one better understands this than Billy Two Rivers, who grew up on the Kahnawake Reserve near Montreal knowing Don Eagle and his family, and eventually learned how to be a pro wrestler from Eagle.

“It’s always been the curiosity of the Red Man in any kind of sport, and he personified it in his career,” explained Two Rivers recently.

“Basically, he was one of the front runners in the television era of wrestling. He was the pioneer in wrestling as an Indian person. Combined with his natural abilities, and the colourfulness of ourselves in costumes, and I guess the curiosity, he was a boom to wrestling, but also he was a role model for a lot of Indian people.”

As a young man, Don Eagle was an iron worker, working on bridges and buildings. He got involved in pro wrestling at the age of 20, following in the footsteps of his father, Joseph War Eagle, who had been wrestling for some time himself, though never a big star. Eagle’s base was Columbus, Ohio and he travelled from territory to territory in a big, long Cadillac that had a 20-foot canoe on top.

Don Leo Jonathan laughed at the memories of his old friend. That canoe was for more than just show.

“He had an outrigger built for that old thing. I’ve been out with him. I used to go out to the reserve, and we used to go to the Lachine rapids, spear sturgeon, shoot ducks and geese. He used it. He was quite a sportsman. Two things that he loved was Indian cornbread and roasted goose.”

According to Two Rivers, Don Eagle was also big on charity. The two Mohawks often visited hospitals and Scout troops together, and he had purchased a property in Vermont where he had hoped to open a boys’ camp. “He was a wonderful person, a giving person. A good person to know,” said Two Rivers.

There was great pride in his heritage too, explained Two Rivers, who lived with Eagle on and off for seven years. “He always made it a point that it was Don Eagle from the Mohawk community of Kahnawake. A lot of times the wrestling announcers would say Don Eagle from Montreal or Don Eagle from Quebec, Canada. And if that was done, he’d correct it. … I took that as an example too to my travels.”

Six-time world champion Lou Thesz remembered Don Eagle as a “very colourful” performer. “He did the little dance. The people were kind of Indian-oriented at that time, and everything was pro-Indian,” said Thesz, whose career began well before Eagle’s and lasted into his 60s. “It was wonderful because he was a good attraction. But when we’re speaking about an attraction, and we’re speaking of wrestling, we’re speaking of two different ballgames.”

“When he was in his prime, he was pretty good,” recalled Hans Schmidt, one of the greatest bad guys of all time. “I’d say he was tall, skinny, no fat on him. He was in pretty good shape when his father was with him, taking care of him.”

Don Eagle’s life on the road was never easy. Racism towards natives was still common. And he liked to drink.

“People never did understand him,” insisted Jonathan. “You take white people looking at an Indian, they look at it completely differently than an Indian looking at an Indian. Since I was raised pretty much around Indians, and with Indians, I understood him a lot better than everybody else. He was just an Indian. He was through and through an Indian, even though he dealt with white people, and he learned to get along in that world, he wasn’t completely accepted in that society, or he didn’t want to be into it. And that’s why people will say that [he had problems]…

“Myself, I never saw him have more than a couple of beers. I know when we were at the Indian dances and stuff in Ohio, I never saw him drink. But that’s not to mean, you know, how people are. Some people have serious problems that people never even know about. Some people function better drunk than they do sober.”

In the ring, Eagle thought that he had hit the top on May 23, 1950, when he beat Frank Sexton in Cleveland, Ohio in a best-of-three-falls match for one of the versions of the AWA World title. It seemed that everything was going his way.

Then three days later, it all came crashing down.

On May 26, he faced off against Gorgeous George on TV in Chicago. This was at a time when world champions never appeared on television, and for some reason Eagle did not wear the belt to the ring.

In his article, Another Indian Bites The Dust, Bill McCormack described what transpired:

“The deed was captured on film with Russ Davis calling the match. The champion dominated George, whose lone offense was a combination of eye gouges and kidney shots of the loosest variety before begging for mercy and submitting to the vaunted death lock to end fall one.

Don Eagle was once more in control when he propelled himself to the floor via a glancing flying shoulder block, only to be counted out with a speedy ten by [referee Earl] Mullihan to even the falls at one per contestant.

It was not long into the deciding fall that executioner [Chicago promoter Fred] Kohler’s trap was sprung. Three quick short rolls using the middle rope for leverage, with a tight grip of the strand, into a backyard cradle, let Mullihan give a quick count with one of the champion’s shoulders clearly off the mat. The Marvelous Mohawk had been gut shot. All hell broke loose.

Realizing the travesty, the former boxer slugged “Evil Earl” and also managed to snare his collar with a free hand as Mullihan fled the ring, ripping his sweaty shirt down its side. Another shot landed to the back of his shoulder blades as he struggled up the aisle to the locker room, and spectators began pelting the ring with debris. A riot ensued.

Gorgeous George, clearly shaken, fought his way from the ring with police assistance. The ring ropes were torn down, chairs flew, and Russ Davis’ closing words to his crew were ‘let’s get out of here.’ “

The crowd rioted at the bogus ending and Eagle was suspended by the Illinois State Athletic Commission for putting his hands on a referee. So a long title reign wasn’t to be for Don Eagle. He continued to hit the road, travelling across North American, almost always a main eventer in major markets such as New York, Chicago, St. Louis, Cleveland, Minneapolis.

Not too long after the title change ‘incident’, Don Eagle took time off to heal his troubled back. He headed back to Kahnawake, and changed the life of Billy Two Rivers forever.

Two Rivers was about 15 at the time, and Don Eagle 25. The youngster fell under Don Eagle’s wing. “He saw some potential in me becoming a wrestler,” said Two Rivers. “He invited me to go back with him when he went back to his training process after his back had healed properly.”

After 13 months off to heal, Don Eagle was true to his word, and Billy Two Rivers made his pro wrestling debut in 1953, after two years of training.

That back trouble would continue to haunt Don Eagle for the rest of his career. In 1963, after three years of wrestling sporadically, he gave it up completely at age 38.

Until March 17, 1966, not much was heard about Don Eagle. Then after that day, he was never heard from again. Don Eagle was dead at age 41 from an apparently self-inflicted gunshot wound.

His friends, Billy Two Rivers and Don Leo Jonathan do not believe that it was a suicide.

“A lot of times when you know a person, there’s just certain things that you figure they would never do. I heard that he had terminated his own life. I find that hard to believe,” said Jonathan.

Two Rivers had packed up from Jim Crockett’s North Carolina promotion, bringing his belongings back home before going to Japan to wrestle. He met the retired Don Eagle just before his death. “I went out and had a couple of beers with him. We talked, and sort of said how things were. He said that he was finding it difficult being retired and his back was giving him a lot of trouble.”

At 5 am, he got the call that Don Eagle had been found dead in his car. “I personally don’t believe that it was suicide,” said Two Rivers. “I have my own conclusions that I draw. Let me tell you safely that it was not enemies. It was not suicide.”

Don Eagle’s name lives on, both in the annals of pro wrestling, and on the Kahnawake reserve. “We have quite an oral tradition here in our community. The names of people that achieve, whether it’s fame or notoriety, are remembered in our community. So he, as a wrestler, his name continuously crops up in talks, discussions,” said Two Rivers.

“When wrestling comes up, or achievement or goals that have been achieved by Indian people or people of our community, he’s well remembered.”

Memories

I read with great interest about your story about Don Eagle. Don and I were neighbors back in Cayuga Falls, Ohio, in the 60’s. At times I would drive him to his matches. What good times we had, on the road and at home with the families, picnics and all. He was a real showman and a great person. It was quite a shock to hear of his death.

Jack Keller