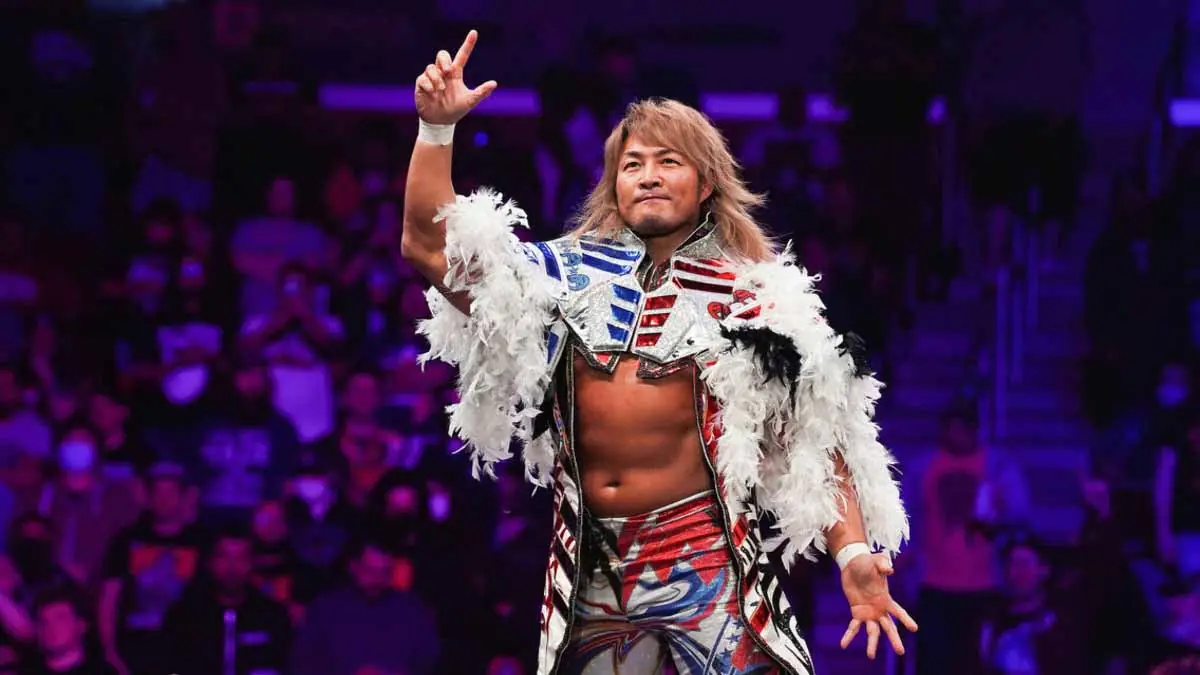

Hiroshi Tanahashi, one of the most successful and industry changing professional wrestlers of the 21st century, has retired from in-ring professional wrestling. His final match took place on Sunday, January 4th at New Japan Pro-Wrestling (NJPW)’s premier event Wrestle Kingdom. With this final match Tanahashi ends a storybook 26-year career defined by in-ring success and overwhelming respect in a profession often defined by jealousy and a “me-first” mentality.

This marked the third retirement of a high-profile Japanese wrestler since 2020, with Jushin ‘Thunder’ Liger retiring at Wrestle Kingdom 14 that year and Keiji Muto having his own Tokyo Dome retirement in 2023, titled Pro Wrestling Last Love. In his last match Tanahashi faced longtime rival Kazuchika Okada for the eighteenth time in their careers and the seventeenth time since Okada became “The Rainmaker”. To show just how important this retirement was, Tanahashi’s match headlined Wrestle Kingdom, the first WK main event since 2007 to not close with a world title bout. Though considering how long and storied Tanahashi’s career has been and how critical he was to New Japan during both the good times and the bad, it’s fair to say that he more than earned this show-closing slot.

Like many people in Japan, Tanahashi was a fan of professional wrestling growing up. By the time he was in high school, however, his interest in that had waned as he focused on other sports. But it never truly disappeared; he still had hints of wrestling fandom throughout that period in his life, especially since he was drawn to wrestlers’ abilities to take so much incredible damage and still go strong.

In his official 2021 autobiography HIGH LIFE, Tanahashi was initially drawn to two specific wrestlers: NJPW’s Keiji Muto and All Japan Pro Wrestling (AJPW)’s Kenta Kobashi. The latter more so than the former as Tanahashi cited Kobashi’s iconic singles match with “Dr. Death” Steve Williams from August 31, 1993 as THE moment that convinced him that wrestling was something special.

“It was the match between Kobashi and Steve Williams that lasted about 30 minutes at the Toyohashi General Gymnasium in Aichi (August 31, 1993). In the end, Kobashi lost, but it was incredible to see him trying to stand up no matter how many vertical drop backdrops he took from Williams. It exceeded my imagination lightly. At first, I was watching without much knowledge, and when I took a fierce lariat or suplex, I thought, “Ah, this is the end,” but then seeing the wrestlers come back, I was like, “They’re still going?!?!” I was thrilled by those wrestlers.” – Tanahashi

But wrestling wasn’t his initial career path. Tanahashi completed high school and enrolled into the Faculty of Law at Ritsumeikan University. While there, Tanahashi had a fateful encounter with the school’s pro-wrestling club when trying to decide on which sports team to join while completing his studies. This was a cross between a fan club and a group of amateurs who practiced wrestling moves, and yet when Tanahashi asked them if any genuine professional wrestlers had come through that school, the club replied ‘no’. Tanahashi, therefore, vowed to become the first.

After completing his studies Tanahashi joined NJPW’s dojo after being scouted by NJPW officials who were always looking for potential recruits with any sort of amateur background. In addition to having experience in freestyle wrestling, Tanahashi also possessed a chiseled physique from his middle and high school days, stemming from his heavy involvement in baseball, swimming, and weight training. It should be noted that, despite no longer possessing this same physique in his retirement match – a physique that was once described as “able to make suits of armor look flabby” – he still looked incredible for a 49-year old with over a quarter-of-a-century of in-ring experience.

Tanahashi joined NJPW at a critical juncture in the company’s – and the sport’s – history. He officially debuted on October 10, 1999 on the same night as fellow trainee Katsuyori Shibata. Three years later the duo would be joined by Shinsuke Nakamura and together they’d become known as The New Three Musketeers of New Japan, in homage to the original famous trio – Muto, Masahiro Chono, and Shinya Hashimoto – who brought NJPW incredible critical and commercial success during the 1990s. At a time when pro-wrestling was losing its wider appeal to shoot-style wrestling (which would later serve as the foundation for Mixed Martial Arts), NJPW struck gold with a formula that saw these outside shooters invade NJPW and take on its defending local wrestling stars. This formula worked for a time, but towards the end of the decade Antonio Inoki, NJPW’s founder and owner at the time, shifted his focus onto MMA at pro-wrestling’s expense. By the time the 2000s began and Tanahashi finished his training and served as an undercard journeyman, NJPW was in a dark period. It was overtaken by Pro Wrestling NOAH as the biggest wrestling company in the promotion and MMA organizations like PRIDE Fighting Championships were outdrawing most wrestling promotions at every turn.

As Tanahashi toiled away trying to find a style suitable for someone called one of The New Three Musketeers, NJPW’s fortunes went further in the wrong direction. Nowhere was this clearer than with the fate of one of Tanahashi’s biggest career rivals, Shinsuke Nakamura. Endorsed by Inoki himself and given a meteoric push to the top as the “Super Rookie”, Nakamura was presented as a generic angry MMA fighter-type in his matches. This was in line with Inoki’s original vision of NJPW and with his continued real fight-inspired “Inokism” mentality, but it was not to the fans’ liking, as seen with massively dwindling audiences and growing fan disappointment as the 2000s wore on.

By 2006 things had gotten even worse. Shibata had left New Japan not wanting to be “a company man”, the Nakamura experiment had failed, and Inoki had lost his majority ownership of his company to Yukes and was effectively ousted from his position. On top of this, an Inoki-driven plan to bring Brock Lesnar in as the new top monster had likewise failed to generate positive momentum, especially following a controversy that saw Lesnar refuse to return the physical IWGP Heavyweight Championship belt after being released, stemming from, in Lesnar’s words, a pay dispute.

So where was Tanahashi in all of this? Wrestling for NJPW like a loyal soldier, of course. But on top of that, Tanahashi was also looking for a new look and a new way to wrestle. Realizing that doing something similar to Nakamura was a mistake since that represented New Japan’s past. To fill the role of headliner Tanahashi had to think about the future. Thus he channeled his experiences from his foreign excursion to Mexico and embraced a more athletic, high-flying, entertainment-driven style. This style saw Tanahashi take bits and pieces of various wrestlers: aside from his childhood favorites Muto and Kobashi, Tanahashi also adopted elements from Tatsumi Fujinami, Ric Flair and particularly Shawn Michaels. The latter was especially noteworthy since, when Tanahashi faced Kurt Angle in 2009 Angle referred to Tanahashi as “Japanese Shawn Michaels”.

“When Kurt Angle referred to me as “the Shawn Michaels of Japan” before our match, I almost let out a joyful exclamation. To be compared to the Shawn Michaels I admire by the respected Angle is an incredible honor.” – Tanahashi

As for the John Cena comparisons, these came from several sources. First, their physiques: both men having almost identical body types for most if not their entire careers. Second, their work ethic: both men devoted everything they had to their respective promotions, wrestling night after night and doing whatever was told of them no matter what out of undying loyalty, all while never giving up. For both men, professional wrestling was an expression of never giving up and Tanahashi, like both Cena and his inspiration Kobashi, wanted the whole world to see this.

“Pro wrestling itself is the ultimate world of self-sacrifice. You take your opponent’s moves, hurt your own body, and make your opponent shine to elevate the match. On top of that, you give your all without abandoning your determination to win until the end, and in the end, you shine as well. This has become my way of life. ” – Tanahashi

Third, their personalities: Tanahashi, like Cena, embraced an overtly family-friendly personality aimed at appealing to all fans, particularly women and children and adopted the catchphrase “I Love You” which he would say to all fans who attended NJPW shows. Fourth, tied to the third, was his initial fan reception: Tanahashi, like Cena, spent several years being vocally rejected by the audience over the way he behaved and his different style being antithetical to what they wanted. And fifth, both men spent long periods in the main event headlining big shows and, in Tanahashi’s case, delivering outstanding, time-tested in-ring classics more often than not.

Over time NJPW’s audience warmed up to Tanahashi’s wrestling and his personality and by 2009 it was time to make him the company’s unquestioned ace, or top star. This happened at Wrestle Kingdom 3 when he faced his childhood idol Keiji Muto in the main event and beat him for the IWGP Heavyweight Championship. With Tanahashi at the helm, NJPW was able to weather a continued storm that ravaged the wrestling landscape in his native country. As all three of the biggest promotions in the country – NJPW, AJPW, and NOAH – struggled compared to halcyon days of yore, NJPW had steadier time going into the 2010s. Tanahashi had many classics during the earlier part of the decade, but it wasn’t until 2012 that things really turned around for him and for his company. For it was in that year that Tanahashi first encountered his biggest career rival and the man with whom he would headline many big shows, Kazuchika Okada.

In February that year at The New Beginning, Okada stunned the world by defeating Tanahashi for the IWGP Championship, ending his reign at 404 days. Okada, like Tanahashi, was a maverick and unproven outside creation, something far more Americanized and gimmicky than anything the fans had ever seen. Yet Tanahashi and Okada had instant chemistry and the two of them went on to have many classics throughout 2012, 2013, 2015, 2016, and beyond. To this day, Tanahashi’s singles matches with Okada are widely hailed as modern classics that not only delivered to the live audience but also brought more attention onto NJPW.

Central to this success and acclaim was how Tanahashi thought about pro-wrestling. Tanahashi believed that every match he had with the same opponent had to be different in some way. This coincided with his personal philosophy of kishotenketsu, a dramatic framework defined by introduction, development, twist, and conclusion.

“When facing an opponent multiple times, there are standard moves that come into play, even if the order of execution changes during the match. This was evident in the Tanahashi vs. Okada match as well.” – Tanahashi

In addition, Tanahashi considered himself a “subtractive” pro-wrestler, one who valued the space between moves and gradually removing things from his repertoire.

“My ideal is “subtractive pro-wrestling,” where the number of moves is limited. My role models are Tatsumi Fujinami and Ric Flair (if we talk about “subtractive pro-wrestling,” Inoki’s pro-wrestling is actually like that too). I have been against the “fast foodification of pro-wrestling,” which aims to put out many moves to excite the audience, and since my time as a U-30 champion, I have been successfully performing matches with a narrative structure.”

Aside from Okada, Tanahashi has also had MOTY-level matches with a wide variety of opponents: Nakamura, Hirooki Goto, Minoru Suzuki, Tomohiro Ishii, Kenny Omega, Kota Ibushi, AJ Styles, Tetsuya Naito, Shingo Takagi, and Will Ospreay. These matches – and others – have earned Tanahashi widespread and admiration, to the point that many of these men appeared after Tanahashi’s match ended to show their appreciation in person, despite not being signed to NJPW (and in Ibushi’s case, hobbling down the Tokyo Dome entrance ramp on a bad leg just to hug and give flowers to the man he once referred to as “a god”).

Tanahashi put on a valiant effort and showed flashes of his in-ring peak during this final match, but alas a win was not in the cards. Still, a tearful Tanahashi got to his feet, only to be showered with respect and admiration from those around him. Aside from Omega and Ibushi coming down, Tanahashi also received flowers from Okada, Jay white, Will Ospreay, several NJPW officials, Shibata (who had a ten-second lock-up and friendly exchange with Tanahashi), and both Muto and Fujinami who watched the final match from the commentary table. After Tanahashi took a group photo with Ospreay, Muto, Fujinami, White, Ibushi, and Omega, Tanahashi received a welcome surprise in the form of recently-departed Tetsuya Naito – another wrestler who long admired Tanahashi – who gave his own brand of thanks in the form of a promo and a fist bump. After this and a small air guitar display in one last moment of fun, Tanahashi tearfully accepted his retirement as the customary ten-bell salute went out signaling the end of his career as an active professional wrestler.

Although Tanahashi’s in-ring career has come to an end, he will continue devoting his time to New Japan Pro-Wrestling as its President. And for anyone curious to see Tanahashi’s in-ring excellence with your own eyes, here is a sample list of Tanahashi’s best matches for you to evaluate his skill for yourselves:

- Hiroshi Tanahashi vs. Hirooki Goto – Destruction 2007

- Hiroshi Tanahashi vs. Shinsuke Nakamura – Wrestle Kingdom 2

- Hiroshi Tanahashi vs. Keiji Muto – Wrestle Kingdom 3

- Hiroshi Tanahashi vs. Giant Bernard – NJPW Soul 2011

- Hiroshi Tanahashi vs. Kazuchika Okada I – The New Beginning 2012

- Hiroshi Tanahashi vs. Kazuchika Okada II – Dominion 6.16 2012

- Hiroshi Tanahashi vs. Minoru Suzuki – King of Pro-Wrestling 2012

- Hiroshi Tanahashi vs. Kazuchika Okada III – Wrestle Kingdom VII

- Hiroshi Tanahashi vs. Kazuchika Okada IV – Invasion Attack 2013

- Hiroshi Tanahashi vs. Tomohiro Ishii – G1 Climax 2013

- Hiroshi Tanahashi vs. Kazuchika Okada VI – King of Pro-Wrestling 2013

- Hiroshi Tanahashi vs. Katsuyori Shibata – Destruction in Kobe ‘14

- Hiroshi Tanahashi vs. AJ Styles – G1 Climax 2015

- Hiroshi Tanahashi vs. Shinsuke Nakamura – G1 Climax 2015 Final

- Hiroshi Tanahashi vs. Kazuchika Okada IX – Wrestle Kingdom 10

- Hiroshi Tanahashi vs. Kazuchika Okada X – G1 Climax 2016

- Hiroshi Tanahashi vs. Tetsuya Naito – Wrestle Kingdom 11

- Hiroshi Tanahashi vs. Kota Ibushi – Power Struggle 2017

- Hiroshi Tanahashi vs. Tetsuya Naito – Dominion 6.11 2017

- Hiroshi Tanahashi vs. Tetsuya Naito – G1 Climax 2017

- Hiroshi Tanahashi vs. Kota Ibushi – G1 Climax 2018 Final

- Hiroshi Tanahashi & Will Ospreay vs. The Golden Lovers (Kenny Omega & Kota Ibushi) – Road to Tokyo Dome 2019

As Rocky Romero and Chris Charlton noted on the English-language commentary for Wrestle Kingdom 20, there is not a single soul on this planet that doesn’t like Hiroshi Tanahashi. The man set incredible standards for himself and carried himself like a consummate professional at all times. It was clear from start to finish that the tears that flowed down his face were genuine, such is how deeply he loves professional wrestling and its fans. To prove this point once again, Tanahashi spent a good twenty minutes if not longer walking around the arena shaking hands with fans, including those up at higher levels.

Without Tanahashi giving everything he had to pro-wrestling every night, it’s possible that NJPW might not still be around today and many wrestlers to have gone through that company – including Styles, Ospreay, and Omega – might not have gotten the attention that helped them reach their own career highs. Tanahashi saved New Japan from the brink of closure in the 2000s by pulling it through the mud with his teeth and through his efforts made it into the top promotion in Japan once again in the 2010s. So it’s fitting that he spends the rest of the 2020s doing office work since he has laid a solid foundation for his successors upon which to build their and the company’s futures.