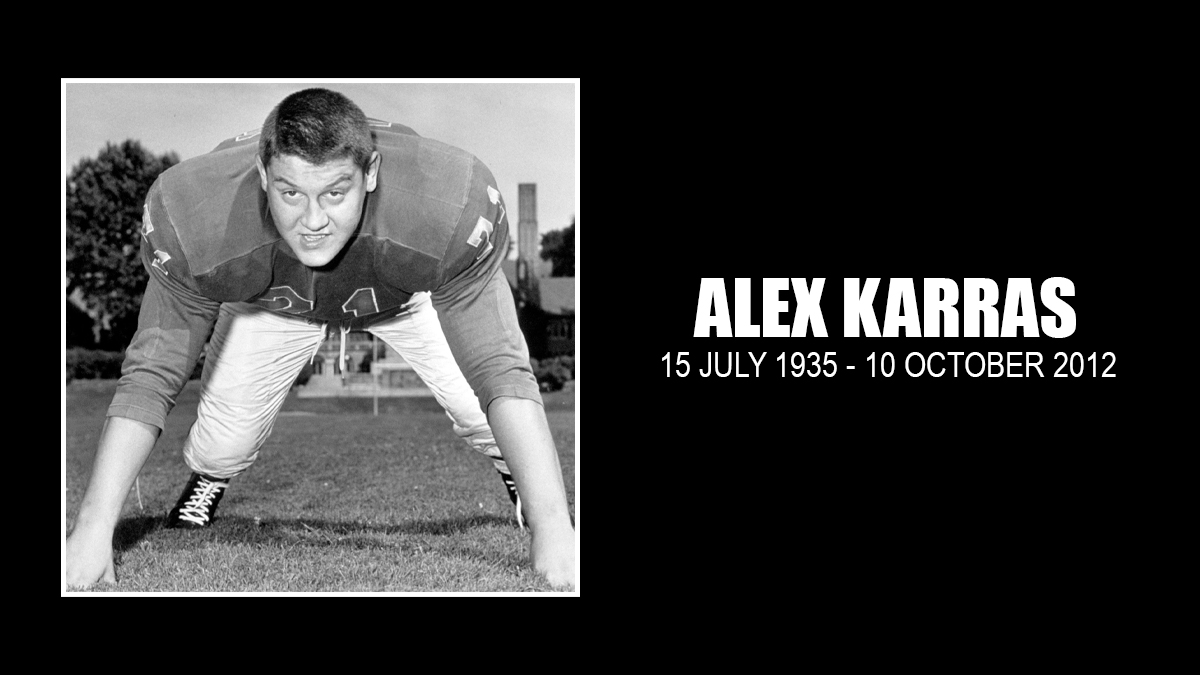

Alex Karras, who died Wednesday in Los Angeles at age 77, is most identified as a National Football League great and an actor. But he was a pro wrestler first, and it was a role he returned to again and again throughout his life, including a major angle with Dick the Bruiser which made national headlines in 1963.

Coming out of the University of Iowa, Karras, a 6-foot-2, 233-pound tackle, had a choice — and he picked pro wrestling.

It was December 1957, and Des Moines, Iowa, promoter Pinky George announced to the press that he had signed Karras to a deal whereby the gridiron star would get $25,000 to wrestle professionally for six months of the year. The idea was that wrestling would not interfere with Karras’ pro football career, which was about to get underway.

Karras never wrestled amateur at Iowa. “He could have been a varsity wrestler,” boasted George, “but he had to keep up his class work and couldn’t spare the time.”

He would wrestle right up until he headed to training camp for the National Football League’s Detroit Lions, though for the next couple of off-seasons, he wrestled sporadically.

Karras was born July 15, 1935 in Gary, Indiana, was was good at basketball and baseball as well as football. At Gary Emerson High School, Karras was selected All-State four times, and played guard, offensive end and fullback. The athletic genes ran in the family — his older brothers were big jocks too: Louis went to Purdue and played for the Redskins; Teddy went to Indiana and played for the Chicago Bears. Their father, Dr. George Karras, died from cancer at the age of 48 when they were teenagers, and Karras learned the value of work, toiling in the a steel mill every summer as a cinder snapper.

At Iowa, Karras was an All-American, but had a rocky relationship with his coach Forest Evashevski — he was kicked off the team seven times — and authority in general. He would play in the Rose Bowl in 1956 and 1957. He was named as the Outland Trophy winner in 1957, his senior year, as the best lineman in America, and came second in voting for the Heisman Trophy.

In the 1958 draft, the Lions took Karras 10th overall, and he played 12 seasons for the team, 1958 to 1970, with a year off in 1963 when he was suspended for gambling activities. Bulking up to 255 pounds, it was once said of Karras, “Other tackles can beat you, but only Karras can make you look like a fool.”

Karras was a first-team all-pro three times (1960, 1961 and 1965) and made the Pro Bowl squad four times.

It was also in 1963 that he returned to pro wrestling with the stunt with Dick the Bruiser.

Karras was suspended for his ties to gambling and organized crime, through his ownership in Detroit’s Lindell AC Bar. He would later admit to placing bets on NFL games.

In April 1963, Karras and Dick Afflis, a former football star who had found success in wrestling as Dick the Bruiser, worked out an angle to draw some attention to wrestling in Detroit. As the story went, Afflis entered the bar owned by Karras and James Butsicaris around 1 a.m., and started badmouthing the bosses. After being refused service, Afflis grabbed Butsicaris, which led to a melee with five other patrons and Karras.

The press ate it up, though Afflis denied that the incident was designed to increase interest in the upcoming wrestling match.

“Let anyone who says this is a publicity stunt get all beat up like this and be taken by the police to the hospital,” Afflis said, who required stitches. “Then let’s see them call it a publicity stunt.” Bruiser was arrested for assault and battery, later getting off with a donation to the Detroit police pension fund; two cops were injured, and filed damage suits in federal court, which garnished his wages in Detroit.

In the match itself, on April 27, Bruiser won in 11 minutes and 21 seconds. “In the early going the Bruiser was bruised, his face bloodied,” reported Ring Wrestling magazine. “The fans were surprised by the remarkable showing that Alex was making. He showed good technique, agility and a toughness that had made him one of pro football’s top lineman.”

It was in Detroit that he met author George Plimpton, who would go the participatory journalism route as a quarterback for the Lions in 1963, and write the famed 1966 book, Paper Lion: Confessions of a Second-string Quarterback. When Plimpton’s book was made into a movie in 1968, Karras got to try his acting chops, foreshadowing a successful Thespian career.

Though the newspapers reported that was his only stint in wrestling during his suspension, and that he gave it up to appease commissioner Pete Rozelle, the fact is that Karras worked more than that one match that spring.

Plimpton went back to football with the 1973 book, Mad Ducks and Bears: Football Revisited, and Karras — “The Mad Duck” — talked about his idol growing up, Bronko Nagurski, who he met on the wrestling circuit:

“Well, years later, the season I was suspended and went into professional wrestling, this one time I went up to Minneapolis for a match. I was late, and I came running into the place and the promoter said, ‘You’re on the tag team tonight.’ ‘Wonderful,’ I said. He didn’t mention my partner on the tag team. So I went down to the locker room. Locker rooms that wrestlers use are different from any other–dingy and small and dirty, and always with this very distinctive smell, a body smell that’s worse than anything you find in places where football and baseball players have been. I don’t know why. Maybe it’s because a lot of wrestlers are big, haystack guys that sweat a lot and maybe take a bath once a month. The smell of wrestlers lies in these little rooms in layers.

“Well, I went down there to change my clothes, and in the shadows I saw this older man practicing with a pair of dumbbells, pumping his arms. I kept looking at him. A much older man. Suddenly it came to me that it was Bronko Nagurski, my childhood idol, standing over in the shadows and pumping these barbells towards the ceiling. I could hardly believe it. I went over and introduced myself; sure enough, it was Nagurski. He was my tag-team partner. I stared at him, bug-eye. Hell, I knew more about him than he did.”

When Karras’ football career ended, his acting career took off. Following a booking on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson in August 1969, Karras found himself on the talk-show circuit and with a number of new roles. As a big man, he often played jocks, and perhaps none better than his three wrestling-related roles:

- In the 1975 TV movie Babe, he played George Zaharias, the wrestler who wooed and wed Mildred “Babe” Didrickson, the greatest woman athlete of them all. Perhaps most importantly, Didrickson was played by Susan Clark, who would become his second wife. (Karras first married in 1958 while still at Iowa.) Clark and Karras would form a production company and put together a number of TV projects.

- In Mad Bull (1977), he was Iago “Mad Bull” Karkus, a famed wrestler who only finds contentment when he finds a woman (Susan Anspach) who saw through the façade and fell in love with him. Other subplots include a stalker fan and Karkus’ attempt to please his father, a former wrestling champion.

- In 1978, he was The Hooded Fang in the movie version of Mordecai Richler’s Jacob Two-Two Meets The Hooded Fang. Karras portrayed an ex-wrestler who had become a prison warden after his wrestling career was was ruined when he was laughed at rather than feared.

Other notable roles included the sheriff in Porky’s, the gay bodyguard in Blake Edwards’ comedy Victor Victoria, and Mongo in Mel Brooks’ classic Blazing Saddles, where he memorably punched a horse. He also was an analyst alongside Howard Cosell and Frank Gifford on Monday Night Football.

But to most, Karras is best known for playing George Papadapolis, the father in the TV hit Webster, which ran from 1983-1989 and starred Emmanuel Lewis as the diminutive Webster Long, and, surprise, Clark as his wife.

In 1984 Karras talked about Webster, which he and Clark co-produced.

“We try to be story-tellers every show. We’ve coped with death, the problems of black and white, stealing and kids being jealous of sib-lings – things that really happen in life,” he said. “What gives us satisfaction is knowing that a lot of schools are telling kids to watch our show and report on it. And, we’re in control of our own destiny.”

In the same article, Karras reflected on many of his acting choices: “I like trying the offbeat roles.”

Away from the stage, Karras and Clark owned property in Ontario’s Georgian Bay area, a 17-acre cattle ranch. “It’s our escape hatch,” Karras said in 1984.

He faced health issues in recent years, and when approached through his production company, interview requests were turned down, citing his unreported battles with dementia.

Earlier this year, the family went public with his battles and Karras took the role of lead plaintiff in a lawsuit against the National Football League, filed in U.S. District Court in Philadelphia, alleging that the NFL didn’t do enough to protect players from head injuries. The case has not been settled.

“All through the time that I’ve been with him, he has suffered headaches and dizziness and high blood pressure and all kinds of things that are … usually the result of multiple concussions,” Clark said in April 2012. “This physical beating that he took as a football player has impacted his life, and therefore it has impacted his family life.”

Then news surfaced on October 8th that Karras had suffered kidney failure and was only expected to live a couple more days. He was released from Saint John’s Health Center in Santa Monica, Calif., to return to his California home on hospice care.

Detroit Lions president Tom Lewand released a statement Monday night regarding Karras.

“The entire Detroit Lions family is deeply saddened to learn of the news regarding the condition of one of our all-time greats, Alex Karras,” Lewand said in the statement. “Perhaps no player in Lions history attained as much success and notoriety for what he did after his playing days as did Alex.

“We know Alex first and foremost as one of the cornerstones to our Fearsome Foursome defensive line of the 1960s and also as one of the greatest defensive linemen to ever play in the NFL. Many others across the country came to know Alex as an accomplished actor and as an announcer during the early years of Monday Night Football.”

“After a heroic fight with kidney disease, heart disease, dementia and for the last two years, stomach cancer,” he died Wednesday, October 10, 2012, surrounded by family, said a spokesman for the family.

Alexander George Karras is survived by his wife, Susan Clark, sons George, Alex Jr., and Peter, and daughter, Katie, as well as numerous grandchildren.