When tragedy short-circuited his wrestling career, Steve Musulin started another.

The 1970s and 1980s star, known to mat fans as Steve Travis, fought back from a drug-related auto accident to prosper in the fitness industry and as an artist specializing in recycling old tools and scrap metal headed for the landfill.

“I’ve always had that creative urge,” Musulin said in a 2006 interview. “I don’t alter pieces– I just put them together like a puzzle. I look for odd shapes that will give me inspiration.”

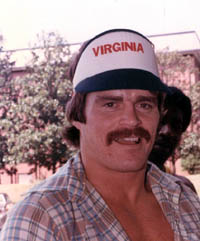

Steve Musulin. Photo by Peggy Lathan

His journey from college football player to wrestler to junkyard junkie ended August 10 when he died at his home outside of Richmond, Virginia. He was 67 and had been in declining health.

Musulin grew up in Charlottesville, Virginia, and played football at Guilford College in Greensboro, North Carolina. There he encountered two situations that would change his life.

At Guilford, Musulin was exposed to steroids. He said Dianabol, legal at the time, made a huge difference in athletic performance. As a freshman, he ran a 40-yard dash in 5.1 seconds and weighed 220 pounds, As a senior, he ran a 4.9-40 at 260 pounds. Musulin was an honorable mention small college All-America lineman in 1974 and first-team All-America in 1975.

“If you weren’t as blessed physically as some others, it allowed you to pursue it more passionately and you had your destiny in your hands,” he SLAM! Wrestling in 2007. “You could do in two years what it would take you six or seven years to do without, and you could do it better.” A powerful man, Musulin finished third in the 1974 North Carolina AAU powerlifting championship and won a heavyweight arm wrestling title in the Tar Heel State in 1976.

While at Guilford, he also met Johnny Powers, the Canadian star who was running the International Wrestling Association on a small scale in the Carolinas. Musulin lived in the same apartment complex as Powers and accepted his invitation to try out the mat as Stonewall Jackson. He wrestled for the IWA for about six months in 1977, gaining experience against the likes of Karl Von Stroheim and Don Fargo, who was doing a Fonzie “Happy Days” gimmick.

Musulin went on to work in the Carolinas for promoter Jim Crockett. He headed to the World Wide Wrestling Federation in late 1978 as Stevie Valiant, the youngest member of the pretend Valiant family, with a promise of a run as a tag team champ.

“The last week I was in for Crockett, I went and had my hair dyed blond and spent about 500 bucks on all this gaudy material, garments and stuff,” he said. But about a week before he headed for the WWWF, owner Vincent J. McMahon brought back Jimmy Valiant, who had been suffering from hepatitis, and put Musulin in the mid-card for a year as Steve Travis.

“Vince Sr. called me to say he made up with Jimmy and he wanted me in as a babyface instead. My big chance was down the tubes. But Vince Sr. kept me in the middle and paid me $1,500 a week as Steve Travis and never beat me on television,” Musulin said in 1994 to the Wrestling Observer.

As Travis, Musulin was named WWWF Rookie of the Year and fought all the big names. Dick “Bulldog” Brower was among his memorable opponents; Brower smashed a table and chairs over Travis’ head in a 1979 match in Binghamton, New York.

His title runs came after he left the WWWF. After a stint in Florida in 1979, Musulin traded the NWA Television Title with Austin Idol in 1980 in Georgia and held the Southeastern tag belts that year with Don Diamond in the Knoxville, Tennessee, territory. He also had a brief run with the NWA Mid-American heavyweight title and returned to the WWWF in 1982 with Rick “Quick Draw” McGraw as the Carolina Connection.

By then, the steroid craze was in full gear. Musulin was in the thick of it as Dr. George Zahorian dispensed all manner of drugs to wrestlers as attending ringside physician at TV tapings in Allentown, Pa., and Hershey, Pa. In the early ’80s, steroids existed in a legal gray area — they weren’t criminalized until a 1988 law that eventually tripped up Zahorian.

“Guys would come out of there with big brown paper sacks of various things. That’s like going to a candy shop,” Musulin said. “Guys would bring in a handful of cash and leave out of there with all kinds of uppers and downers and pain pills and injectable steroids, oral steroids, testosterone. Everybody would kind of research it on their own and come up with their own ideas.”

He also spent 1983 in the Carolinas wrestling for the Mid-Atlantic promotion under his real name. The following year, the fast and loose steroid days of the 1980s cost him his livelihood. Under the influence of Placidyl, a hypnotic he obtained from Zahorian, later convicted of steroid distribution, Musulin blacked out behind the wheel in Atlanta and struck and killed another driver.

Musulin was hospitalized for several months with a spinal cord injury that would limit his mobility for the rest of his life, then served nine months in a Georgia prison for vehicular homicide. McGraw died of a heart attack in 1985 after overdosing on the same drug.

Back in Charlottesville, Musulin joined the staff of ACAC Wellness and Fitness, working there for 29 years. He also shared his life lessons with young people, warning them about the dangers of drug abuse and the toll it can take. “And nothing’s changed,” he said after the infamous Chris Benoit murders in 2007. “Guys die from it. They died from it back then; they’re still dying from it now. It looks like the stakes might be a little bigger now because of sex, drugs and rock and roll, but it’s all in pursuit of being successful in your chosen business.”

A memorial service for Musulin will be held at 2 p.m. August 25 at Mount Vernon Baptist Church Memorial Park Chapel in Glen Allen, Virginia. The family has requested contributions to the Charlottesville SPCA in lieu of flowers.