Rolland “Red” Bastien, who died August 11, 2012, after a lengthy battle with Alzheimer’s disease, was one of the best pure talents ever in professional wrestling, one of the best trainers ever — and one of the most notorious merrymakers as well.

After all, well into his 70s, his Christmas cards with his companion Carol McCutchin bragged about Red just barely “Staying Ahead of the Sheriff!”

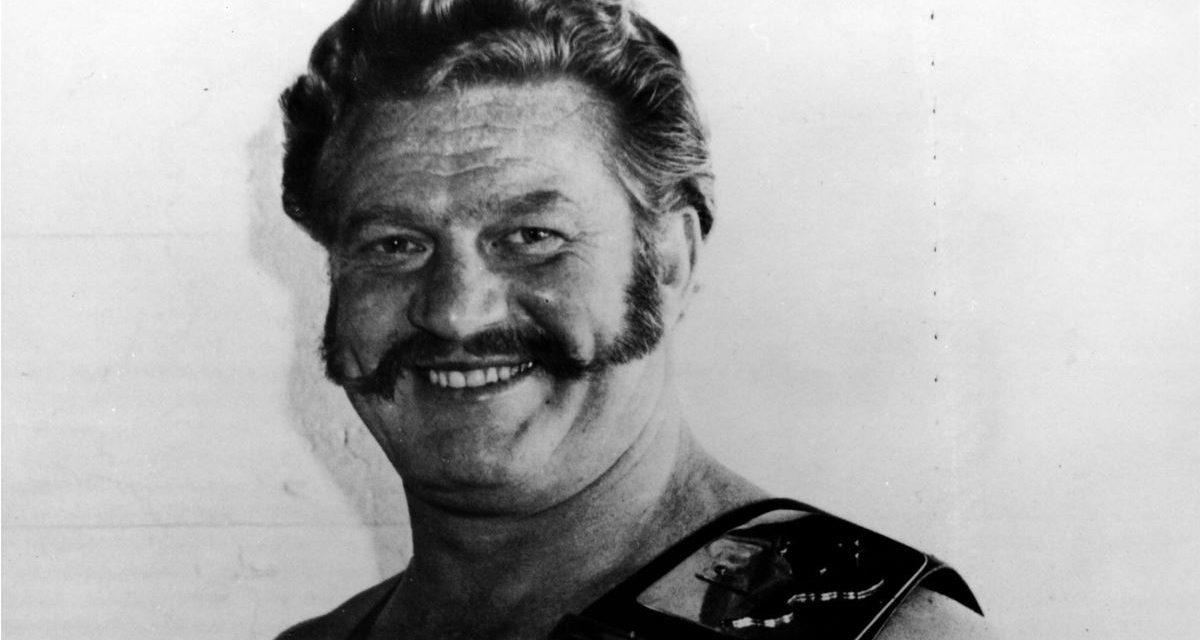

Red Bastien. Courtesy Chris Swisher

There was the backhoe that he and Ray Stevens managed to get into a new hotel lobby. Or the cab driver they got drunk and hung from a flagpole.

Bastien once described Stevens to this writer: “He was exuberant. He didn’t care about anything. He just went through life and lived the life. Viva la vie, he picked up that expression, Viva la vie. He did, to the fullest.” That may well have been Red’s life as well.

“[Red] got me into a lot of trouble, and he got me out of a lot of trouble,” confessed Fritz von Goering.

Or, in the words of contemporary Paul Diamond, “Red Bastien is a real cartoon,” a real-life Bugs Bunny. “He’s got great stories.”

Born in Bottineau, N.D., on January 27, 1931, Bastien went to Roosevelt High School in Minneapolis. He swam briefly for coach Toivo Jambeck. “I remember he was a nice friendly boy with with a very pleasant smile … and a good swimmer. I could see a great deal of potential in him. But after his sophomore year he didn’t show up for swimming practice any more,” Jambeck said in a 1971 interview.

Bastien wrestled in high school, but never got into it. Instead, he started training at 16 with old pros at Citizens Club in Minneapolis, because he wanted to be a pro wrestler right away. “I wasn’t even remotely interested in amateur wrestling,” Bastien said. Key trainers were family friend and top middleweight Henry Kolln, who taught Red in a Minnesota sawmill, and Einar Olsen in Wisconsin.

The first recorded match for Bastien is in late 1949, but he wrestled for cash before that when he was about 16. According to Bastien, his first bout was at the Grand Café in Minneapolis when someone no-showed. He knew a ref, who asked him to wrestle Swede Oberg.

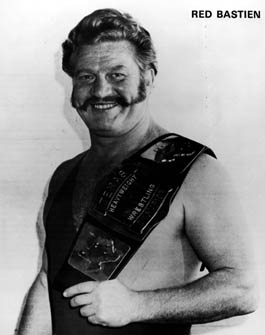

Red Bastien strikes a pose. Courtesy Chris Swisher

Shortly thereafter, Bastien started on the carnival circuit, which had athletic shows, referred to as AT shows. He was 16 years old when he worked for Bodart’s Shows in Minnesota, North Dakota, and Wisconsin, and weighed in at 145 pounds.

In an interview with historian Mark Hewitt, Bastien talked about his life on the carnies. “Most of them were middleweights, but they would wrestle anyone … These were old-time wrestlers … They’d been around the mat world for years, so it wasn’t likely that they were going to be beat, no matter how big the guy was. They had what they called submission holds, and if he didn’t give up, he’d get his leg broken.”

There were days he had eight or 10 bouts. “I never got beat in the carnival. It was pretty hard to beat someone with any basic knowledge of wrestling,” he said.

He migrated to Chicago and booker Billy Goelz used him as someone with potential, but duty called. Bastien served in the Navy during the Korean War, working with a repair squadron for the Sixth Fleet, stationed near Naples, Italy. During the time abroad, he got to visit different gyms in Europe, where he picked up some Greco-Roman wrestling.

Back in the States, famed wrestler Joe Pazandak of Minnesota took an interest in him. Bastien was wrestling at the Marigold in Chicago. “I’d worked out with him a number of times at the Y, then I took him over to the University of Minnesota and worked with him there quite a few times,” Pazandak said in a 1971 interview. “Red got to be very, very good. He was light, but he moved fast.”

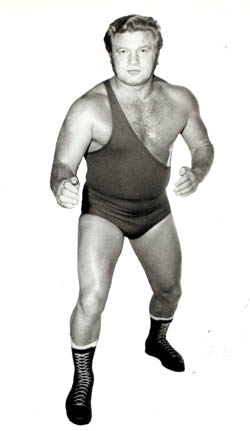

Red and Lou Bastien. Courtesy Chris Swisher

One of his first territories was Charlotte in 1957, but it wasn’t a good fit, said Bastien. “They didn’t live up to their promises,” he said of the Jim Crockett promotion. “I had worked in New York a long time in and out, so I’m thinking I want to do something different.” Bastien approached Capitol Sports promoter Vincent J. McMahon and suggested a tag team. “I’m thinking if I’m going to get a partner, I might as well get a brother.” Bastien paired up with Lou Klein as Red and Lou Bastien — both had red hair — so a brotherhood made sense. And Klein’s mat skills contrasted nicely with Bastien’s aerial arsenal of dropkicks and flying head scissors.

In 1960, the Bastiens became a top draw in Capitol Sports, and also in Chicago, where McMahon traded talent with promoter Fred Kohler. They held the U.S. championship, the highest Capitol Sports tag title, three times, twice swapping it with Eddie and Dr. Jerry Graham, and once besting The Fabulous Kangaroos.

The Bastiens also held the Indiana version of the AWA World tag team title two times. By 1962, Bastien, a tag specialist at 5’10” and 200 pounds, moved on, tired of Klein’s desire for more fame and his pennypinching.

All told, Bastien might be one of the greatest tag team wrestlers in history. During his career, he held one-half of 13 tag team championships with 10 different partners. “Red Bastein was the closest to anyone who had the art of knowing what you were going to do next,” Dick Steinborn said in The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Tag Teams. “It was so simple teaming with Red, that it wound up not being a chore.”

Probably the best known team was the “Flying Redheads” with Billy Red Lyons (Bill Snip). During their runs together in Midwest and Texas, Bastien and Lyons showed that the greatest gimmick of all was true wrestling ability.

“There was no greater than Red Bastien and Red Lyons. They were the greatest team of all time. There is no other team,” said frequent opponent Blackjack Mulligan. “If you ever saw Red Lyons and Red Bastien wrestle the Vachons, wrestle anybody, you had pure tag team wrestling at its basic. There’s no better, there never will be. They set the bar so high that all we could ever do is to try to achieve a small degree of their success.”

Bastien and Lyons were old hands by the time they first teamed up in 1969 in the midwest-based American Wrestling Association. A little undersized to be considered top singles contenders, they were ideal companions in and out of the ring. “Our styles were similar. We got along so good, too. That’s more than half the battle. Red and I got along super, never had one word between us,” Lyons said.

Red could refer to blood as well. Lyons got cut bad in one TV match against the Vachons and Bastien took him to hospital. Lyons had a sheet on him, with an open eye hole for patching it up. “Billy, it could have been a lot more serious than what it was,” cracked Bastien. Lyons asked how could that be. Red: “Well, it could have happened to me.”

“He was a good partner for me,” Bastien said. During travels from Winnipeg to Omaha, Neb., “we never had a cross moment in the car. At that time, you were with your partner more than your wife. Billy Red was a very good person.”

Bastien was involved in one of the biggest tragedies in wrestling history. He had been teaming with Hercules Cortez (Alfonso Carlos Chicharro) in the AWA since 1969, and the duo had knocked off the Vachons for the tag titles on May 15, 1971, ending their almost two-year reign of terror. But just six weeks later, Cortez was dead at 39 and Bastien lucky to be alive.

The wrestling crew was on its way back to Minneapolis from Winnipeg on July 23, 1971. Moose Morowski was speeding along the interstate with Bull Bullinski asleep beside him. He figures he was going about 85 miles an hour late at night, and was surprised when another car zoomed past. Twenty-five miles up the road, he came across the car again, this time in a wreck on the side of the highway.

Morowski pulled Bastien from the crash. “The only thing that saved Red Bastien’s life was that he didn’t have his seat belt on, and he slid underneath the dashboard,” Morowski said. Next, he and Bullinski went looking for the driver. Cortez was about 75 feet away from the accident. “There was not a scratch on him. I guess when he had flown out of the car, he landed on his head, or he broke his neck and died instantly.”

Bastien has fond memories of Cortez, and they had discussed big plans as a tag team. “He was so charismatic when he was wrestling in the ring, even though his feet never left the ground. He was so vibrant,” Bastien said. Red would do the high-flying and Hercules was the powerful hulk. “I knew right away that it was going to click. After out first match, I said, ‘Man, this is could be good,'” Bastien continued.

The sudden death of one of its champions forced the AWA to act quickly. Cortez had been scheduled to wrestle Nick Bockwinkel in Minneapolis on July 24, and AWA champ Verne Gagne filled in for a non-title match. Ray Stevens debuted on that same show, and came to the ring with Bockwinkel for the first time, a preview of their great team. According to the storyline, Bastien was allowed to “choose” a new partner, and was soon lining up with The Crusher (Reggie Lisowski).

Despite his close call, Bastien was back at work almost immediately. “I was not really very good after that [the accident]. I was fortunate to get out of that wreck. I went right back to work.” A short time later, he asked for some time off and went to Mexico for a respite before returning to the ring, dropping the titles to Bockwinkel and Stevens in January 1972.

In 1979, Bastien started promoting in Modesto, Calif. He was a visionary in many ways, bringing lucha stars such as Konnan and Rey Mysterio Jr. to California to perform.

As a trainer, working with partner Bill Anderson, Bastien brought a few names into the business: Sting (Steve Borden), Ultimate Warrior (Jim Hellwig), Angel of Death (Dave Sheldon), Steve DiSalvo, and the lesser known Mark Miller and Garland Donoho. Four of them — Borden, Hellwig, Miller and Donoho — would be promoted briefly as Powerteam U.S.A.

Away from the ring, Bastien took up scuba diving and loved to use his underwater movie camera in Florida so he could film in the deep.

For all the accolades in and out of the ring, no story on Red Bastien is complete with a mention of “The Bishop” — Red’s, ahem, member. There might be more stories about The Bishop than the man himself, and, like Red, it has been described as larger than life.

Nick Bockwinkel tells a story about Bastien mailing him “a mechanical sketch, a top view, side view and end view with all dimensions — length — width — weight, of the male appendage” in an attempt to have him set Red up with a prospective paramour.

Perhaps the most recounted stories of Red’s unit have to do with his battles with Johnny Valentine — outside the ring. Bastien got drunk one night and fell out of the car, and JV peed on him while he was down. Years later, when Valentine was on crutches, they stopped by the side of the road. JV fell down with the crutches and Red came over. “Johnny, remember that time? Well, here’s your payback.”

“He laughed the whole time through,” recalled Bastien.

Lou Thesz, John Swenski, Red Bastien and Pat Patterson at a Cauliflower Alley Club reunion in 1996. Photo courtesy Joe Pottgeiser.

As the president of the Cauliflower Alley Club from 2000-07, it was Bastien’s job to be visible and stay in touch with old friends. Could there be a better job?

“He does so much for wrestling. He goes all over the world,” said Mad Dog Vachon

Bastien would hit all the induction ceremonies he could, travelling extensively with his companion Carol. Part of the year was spent on their boat, moored in Anacortes, Wash. In 1992, he started the annual Red Bastien’s Texas Shoot Out in Dallas, helped by Larry Dwyer, which brought together many oldtimers from the Lone Star State, and mixed them in with current independent wrestlers for a fun evening.

In 2007, Bastien was inducted into the George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame at the Dan Gable International Wrestling Institute and Museum, and that same year, the CAC began the Red Bastien Friendship Award, given to a “super fan” who contributed much to professional wrestling.

Alzheimer’s started to take its effect in the late 2000s, with Bastien able to recount — with great vigour — stories from the past, but unable to recognize people or remember what happened moments ago. In 2010, he was admitted to a long-term care facility in St. Paul, Minnesota, where his daughter, who is a nurse, could oversee his care.

“I’ve lived a helluva life,” Bastien said. “The only thing I ever worried about was that I’d get killed on the highway. And it happened to Hercules.”

He passed away on Saturday, August 11, 2012.

RELATED LINK

Mat Matters: Remembering Red & Carol, king and queen of the CAC