Luke Graham’s system for audience involvement was simple and enormously effective. When a ring announcer, interviewer, or fan described him as “Crazy Luke,” Graham loudly retorted that he was perfectly sane, that there was not a touch of insanity in him. Immediately, crowds shouted “Crazy Luke, Crazy Luke,” prompting Graham to recoil in horror, and cup his ears to block the noise.

For nearly 25 years, Graham used his craziness to incense fans, batter opponents, and win titles around the world. And while friends and colleagues said his ‘crazy’ persona fit him perfectly, they also remembered Graham, who died Friday, June 23, 2006, at 66, as a fun-loving, soft-drawled, gentle man.

“He was the original ‘crazy’ guy. It wasn’t really a gimmick,” said Luke Graham Jr., his wrestling son, who, for all intents and purposes, was his son in real life, as well. “The best gimmicks are those that are pretty close to the real thing. If you really knew him, you know he jumped out of his skin if the phone rang and he was near it. He was the world’s biggest ribber. What you saw in the ring was Luke Graham.”

Graham was born James Grady Johnson, February 5, 1940, in Union Point, Georgia, near Macon. A wrestling fan growing up in Georgia, he was captivated by Dr. Jerry Graham during matches in Macon, especially the controversial doctor’s long and bloody feud with Chief Big Heart. “Dr. Jerry was always one of my idols,” Luke said in an interview for The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Tag Teams. He started wrestling in the early 1960s, and was working as Pretty Boy Calhoun and under a mask in Tennessee when wrestler Frankie Cain suggested he hook up with Jerry because the two looked so much alike. Cain recounted his conversation with Johnson to wrestling writer Scott Teal: “If you want, I can call him and see if he’d want you to work with him as your brother. You could make a ton of money.”

Jerry jumped at the notion and brought Luke to the Calgary-based Stampede promotion in 1963. The pairing was perfect, as Luke took the place of Eddie Graham, who had moved to Florida, turning the Grahams from a pair of tag team “brothers” into wrestling’s first family of mayhem. They also wrestled in the Maritimes that summer, where Luke got a chance to replace Jerry in bloody battles against Chief Big Heart.

The following year, the red-hot team headed to the WWWF, winning the U.S. tag team title from Don McClarity and Argentina Apollo and holding it for eight months. “When Jerry brought me in, I came in as ‘Crazy’ Luke. Going ‘crazy’ was the best thing that ever happened to me,” Luke said. They also wrestled a few six-man matches with Eddie. Luke attributed the appeal of the brothers to action and violence. “We gave them blood and guts, which I think everybody wanted to see. You go to a bullfight to see the blood. I think that’s why people came to see the Grahams.”

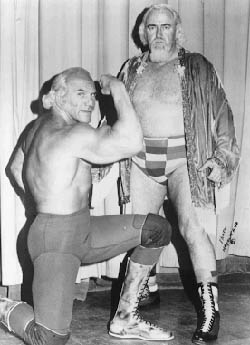

“Crazy” Luke Graham and “Superstar” Billy Graham (kneeling). Photo courtesy Chris Swisher

With his bleached hair and goatee, Graham struck out on his own in 1965 to become the WWA world champion in Los Angeles, swapping the belt with Pedro Morales. “It was time for me to be a singles wrestler. I always did a lot of tag team wrestling, but ‘Crazy Luke’ was probably better for singles wrestling,” he said. A master of the taped thumb, he jabbed opponents from coast to coast, leaving them breathless and prey for a pin. During his career, he headlined everywhere he went and held championships in territory after territory, including the Hawaii heavyweight title (1968), the Georgia heavyweight crown (1974), and the Central States belt (1984). “Luke Graham was one of the nicest guys I ever worked with. As a referee, he would work with you and never make you look stupid,” veteran Georgia referee Bobby Simmons recalled for OldSchool-Wresting.com.

Graham also added several tag team belts to his collection. When the WWWF created its world tag team title in 1971, he moved from Georgia to pair with Tarzan Tyler as the first champions; they had a six-month run as titleholders, feuding with Chief Jay Strongbow, Gorilla Monsoon, and WWWF champion Pedro Morales. He also shared world tag team titles in the Los Angeles, Detroit, and Tennessee promotions. “He’s probably one of the most underappreciated guys in the business. He could put butts in the seats. He could work with just about anybody, make them look good and get over himself,” Luke Jr. said. “He was not always a company guy, which hurt him sometimes, but he was one of those guys who made wrestling what it is and helped to build New York.”

Some of Graham’s antics, revolutionary at the time, were quickly picked up by other wrestlers. His wild-eyed looks, facial expressions, and manic persona were precursors for stars like Lonnie Mayne and the Moondogs, and Ernie Ladd openly attributed his use of the taped thumb to Graham. “He never had anything but appreciation for those who did those things. When he read in an interview a couple of years ago that Ernie said he had picked up the taped thumb from it, his chest swelled a little, to be honest. He was a proud man, but his ego was never overinflated,” Luke Jr. said.

Dean Silverstone used Graham as U.S. champion in his Pacific Northwest promotion in 1974 and recalled a rib that Graham good-naturedly accepted. The promotion paid for his plane ticket from Atlanta to Seattle and promised him $1,200 for his work.

“He arrived with 33 cents in his pocket, so someone told him that this office pays off one week after the event takes place,” Silverstone recounted. “He panicked and started borrowing spare change from the boys and from the fans. After his final show, he came into the office and asked if he could get currency for his 20-plus-something dollars he had begged for in coins. His pockets were pulling his pants down. I remember his face when we paid him off his guarantee, but I made him keep his coins. Luke was a great worker.”

“Crazy” Luke Graham. Photo courtesy Chris Swisher

Outside the ring, Graham was very different from the rabble-rousing Dr. Jerry, who filled police blotters for more than 30 years with wild, often alcohol-induced antics, until his death in 1997. “He taught me a lot about the psychology. But the good doctor was a handful to keep up with. Being his brother was definitely a challenge. You were better off not trying, really,” Luke said with a laugh in the interview for the Tag Team book. Added Luke Jr. of his father: “While he could be flamboyant and off-the-wall in the ring, he was a real quiet person at home. He was a man who, if you knew him, you couldn’t help but be in awe of him — a real caring, sensitive type of guy that never took himself too seriously in the later years.”

In fact, Luke’s diversions were definitely more moderate than those of his older brother. He enjoyed locker room ribs — “You’d tell him a joke and he’d have this absolute deadpan expression. No reaction at all, like he found nothing about it remotely funny. Then, the next day, you’d find him repeating the joke to somebody and telling it a heckuva lot better,” said Luke Jr.

Graham also was an inveterate gamesman, alternately lining and deflating the wallets of wrestlers playing cribbage and poker. “He would gamble on anything,” said Ron Martinez, who used Graham for a hot program with Ernie Ladd in the National Wrestling Federation in 1972. “He was a big time Las Vegas lover like I am … I remember I lost $150 to him one night before a match. I paid him back years later when we both visited Las Vegas at the same time.”

Graham retired in the late 1980s, though later he managed and teamed with Luke Jr. In 2001, they attempted to build a national, publicly traded company named Galaxy Championship Wrestling, based on an Arkansas promotion, but that effort wasn’t successful. The duo attended the Cauliflower Alley Club reunion in 2001 and wanted to return, but Graham’s health, which deteriorated sharply in recent years, would not permit it. He had a pacemaker installed several years ago and underwent surgery at a Macon hospital one week ago. Graham briefly showed signs of improvement, but the ailments associated with congestive heart failure — and a lifetime of hard living on the road — were too much to overcome.

“Right to the end, he was fighting because he was a fighter,” Luke Jr. said. “He kicked a ventilator on the way out.” Graham’s boots were placed in the ring while a 10-count tolled at an Arkansas independent show Saturday, Luke Jr. said.

Graham also is survived by four daughters, a son, 11 grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren. A funeral service will be held at 11 a.m. Monday at Williams Funeral Home in Milledgeville, Ga. Luke Jr. said boots, tights and a brass knuckles belt that his dad treasured will be sent off with him.