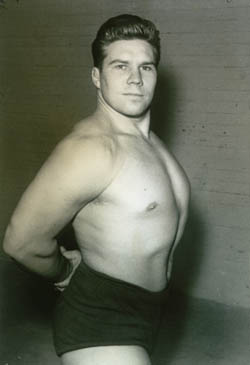

George Gordienko was one of the most interesting and intriguing persons ever to come out of Canada – pro wrestler turned painter. His work, on both types of canvases, is well-known in Europe, but not in Canada. So his nephew is trying to change that.

Ted Gordienko took care of his uncle George for the last year of his life, until his death in May 2002 at age 74 from melanoma cancer. He is also in charge of much of his uncle’s artwork.

George Gordienko

Now, Ted Gordienko has embarked on a new project. He is piecing together a documentary on his uncle, focusing on his art, but also his wrestling. He has been interviewing people that knew his uncle, and gathering footage of his wrestling career.

“He had a passion his whole life for art,” Ted said of his uncle. “I don’t think he would have became the artist he was without wrestling.”

George Gordienko is one of those special examples that wrestlers are more than brawn.

Out of Winnipeg, Gordienko fell under the spell of the great amateur Ole Olsen at 15, which led to his pro training under Joe Pazandak. After debuting after World War II, he was dubbed ‘Wonder Boy’ early in his career, and also worked as Flash Gordon. Early stops included San Francisco, Buffalo and Minneapolis. He quickly gained a reputation as one of best shooters in the business.

George worked in Calgary for Stampede Wrestling off and on many years, willing to go visit his old friend Stu Hart.

Cowboy Dan Kroffat was one of the workers that got to travel with Gordienko around Western Canada. “what a prince of a man. He was truly a man’s man. I traveled for hours and hours and hours, and he rode in my car with me. We were always talking, traveling across the Praries. The more I got to know him, the more I admired him and respected him because he was almost a scholar. This guy was intellectual, he was an artist, he was well-read. He was really before his time in so many ways,” Kroffat said. “The most ironic part was that he was extremely a tough guy. But boy, he had a Clint Eastwood approach to life. Just low-key, unassuming. But if you messed with him, he’d pull out the 45-Magnum with capability. He was truly one of the tough guys in the business. I mean real tough guy. Everyone was afraid of him, admired him, respected him. But he did it all very quietly. He was very unassuming. He was just truly a gentleman.”

But it was overseas, in Europe, the Middle East, India, Australia, New Zealand and South America, that he took off as a wrestler and gained fame, where his skills were respected. He worked before massive crowds in Iran and India (as Firpo Zyzbsko) especially.

Kroffat recalled a story from England. Gordienko had a top hat, coat, and cigar in his mouth when he went into a gym. “He took the weights off the bar, pressed them, then put them down and walked out of the gym? … He took 300-pound weights off the rack, these guys were doing them. Gordienko just picked the weights up, right off the rack, threw them up in the air over his head, put them down. He had his top-coat on, and quietly walked out the door. Everyone’s mouths were wide open.”

Wrestling Review from August 1970 wrote of Gordienko almost with awe. “Gordienko, a giant figure of a man, must surely be one of the strongest wrestlers in the world. Very few of our English wrestlers have been able to defeat this heavyweight from Canada.”

Paul ‘The Butcher’ Vachon was with Gordienko in India. “The Indian wrestlers, they had a big reputation. If you go to India, watch out for them Indian wrestlers, they’ll hurt you. He went there, and Gordienko beat them all, beat them all.”

After Vachon had been to India, he asked Gordienko what he thought of Indian wrestlers. “In India, wrestling was almost a national sport. They fancy themselves the greatest wrestlers,” Vachon said, before continuing. “Gordienko says, ‘Greatly overrated.’ Because I had heard the story – he had stretched them all.”

Gordineko loved to see the world. He explained some of his travels, and artistic training, in a story in the Cauliflower Alley Club newsletter. “I took a train to Rome, Florence, and Paris. I spent a few weeks in Paris – and loved it. From there I went to London. I stopped there a fair length of time – ’til my money ran out. I attended St. Martin’s School of Art and had Anthony Caro as an instructor in sculpture. Caro became internationally famous and was knighted for his work.”

There’s a great story about Gordienko and Picasso as well. It turns out that the famed artist Pablo Picasso was a wrestling fan, and when he got the chance to meet Gordienko, he jumped at the chance. Of course, Gordienko was equally thrilled to meet Picasso.

After further training in art, Gordienko settled on Vancouver Island, off the British Columbia mainland, and lived a life of a hermit, painting and sculpting.

“He wanted to be known as an artist,” explained his nephew, who believes that, in the end, his uncle was 100% happy with the choices he had made in his life, that people “thought of him as a clown not an artist … that’s why he was a little bit bitter.”

Ted Gordienko’s goal is to find a grant or some funding to complete the documentary properly. He is a chef in Victoria and has found this side project to be fulfilling in a whole new way. His father, Goodie, worked as a pro wrestler and referee for a bit as well, and they all were surrounded by wrestling throughout their lives.

The fact is that Gordienko’s paintings can go for tens of thousands of dollars, yet is a virtual unknown in his own country. “It’s a shame (that he’s not well-known). I think we have to be careful how we portray it because people should know who he is,” said Ted Gordienko.

RELATED LINKS

- Dec. 20, 2022: George Gordienko finally has his day with great biography

- Apr. 28, 2022: BC police on hunt for stolen Gordienko art

- Apr. 25, 2022: Gordienko was destined to be an artist

- Jan. 17, 2022: Thesz wanted Gordienko, not Watson, to win NWA title in 1956

- Jan. 10, 2022: Gordienko: Canada’s top wrestler worldwide from the 1950s-1970s

- Buy George Gordienko: Canadian Wrestler, Artist and Renaissance Man at Amazon.com or Amazon.ca